The stories of African Americans in and around the Morris-Jumel Mansion are a microcosm of the history of enslavement, abolition, and Black excellence in eighteenth, nineteenth, and twentieth century New York City. Enslaved persons enabled the estate’s success and prosperity when it was first colonized as a Dutch farmstead once owned by Jacob Dyckman and later used as a country retreat for Roger Morris and his family. The Revolutionary Era figured heavily in the Mansion’s history and brought free and enslaved African Americans together under its roof. Their interactions speak to the evolving nature of enslavement in a city whose ambivalence around African bondage continued for another fifty years. After the official abolition of slavery in New York in 1827, slavery did not vanish from the New York Black experience, as there was a burgeoning business of kidnapping free persons of color for illegal sale in the South. It was here at the Mansion that Solomon Northup’s wife, Anne, lived and worked as a cook after her husband had been kidnapped and illegally enslaved. The Mansion’s surroundings remained rustic, worked by tenant farmers until the 1880s economic boom brought the encroachment of middle-class development which catered solely to white families. But by the 1920s, this demographic began to give way with the advent of the Harlem Renaissance, a period which induced prosperous and prominent Black families to move into the newly unrestricted luxury high-rise apartment buildings comprising the apex of “Sugar Hill,” that still surround the Mansion today.1

Our Stories: Black Histories at the Morris-Jumel Mansion

Introduction

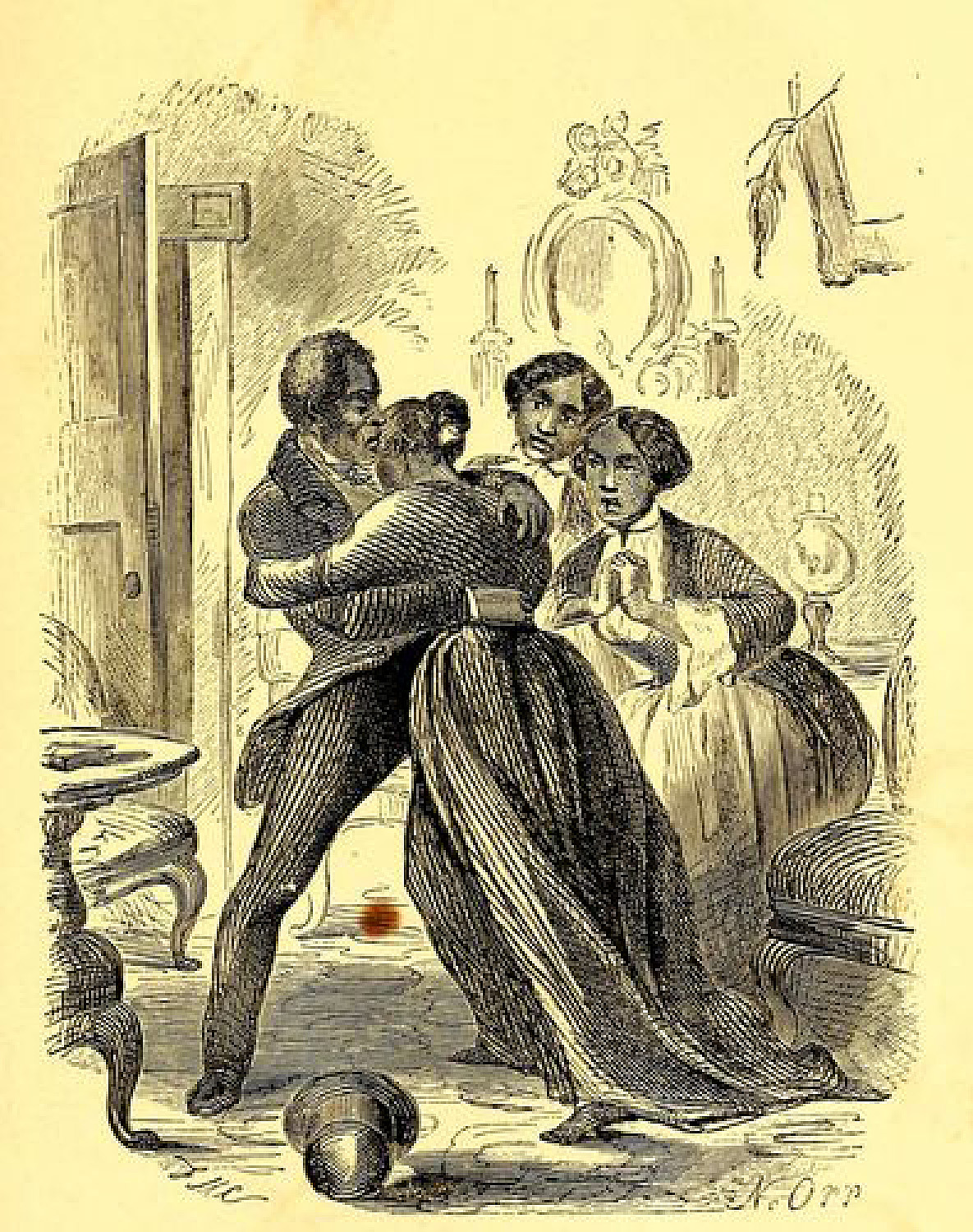

Nathanial Orr, “Arrival home, and first meeting with his wife and children.” Originally published in Twelve Years a Slave. Buffalo N.Y.: Miller, Orton & Mulligan, 1853

Anne Hampton Northup (ca. 1808-1876)

Anne Hampton Northup was born around 1808 in Sandy Hill (near Saratoga Springs), New York, to free-Black parents who were property-owning citizens. Despite the legal racial classification as Black as indicated in some census records, the family claimed Black, White, and Native ancestry 2. On Christmas Day 1829 Anne married Solomon Northup, a professional violinist, with whom she had three children: Elizabeth (b. 1831), Margaret (b. 1833) and Alonzo (b. 1836). However in 1841 Anne’s husband suddenly and mysteriously disappeared while in Washington, D.C. for a musical engagement. 3

Anne Northup began working in domestic service in her teens and was renowned for her skills as a cook. She was working at Sherrill’s Coffee House in the spa town of Saratoga, New York when her husband, Solomon, was kidnapped and sold into slavery in 1841 4. Solomon was able to send Anne a letter when he reached New Orleans, informing her that he had been kidnapped. However, despite a 1840 New York law, which intended to help return free New Yorkers illegally sold into slavery, the state’s governor claimed he could not do anything to help the Northup family, as they did not know his location after being sold in New Orleans.

During the period of Solomon’s unknown whereabouts, Anne became her family’s sole provider while trying to locate and rescue her missing husband. During the summer of 1841, Eliza Jumel hired Anne Northup and her children to work at the Mansion, in New York City. Anne Northup’s acceptance of Eliza’s employment offer may have been a strategic decision because it would have allowed her to keep her family together, increase her income, and better advocate for her husband’s rescue.

During the Northup family’s time at the Mansion, Anne Northup worked as a cook, and her daughters, Elizabeth and Margaret, as ladies’ maids. Her son, Alonzo, trained to become a liveried footman, a uniformed servant whose duties may have included greeting visitors and waiting at table. Evidence suggests Anne Northup likely moved out of the Mansion with Margaret and Alonzo in 1842, while Elizabeth remained in service to the Jumel family 5.

Anne Northup signed documents with an “x,” suggesting she was illiterate. Much of what we know about her family’s history at the Mansion comes from court testimonies during the battle among Eliza Jumel’s heirs over the Jumel estate. In the trial documents of the Bowen v. Chase case, the Northup family testified that Eliza Jumel frequently referred to the Northup children as her own, calling Elizabeth “daughter.”

In addition to the trial records, a glimpse into life from the Northup family’s perspective is provided from the acclaimed 1853 memoir, Twelve Years a Slave, which Anne’s lost husband wrote within months of his restoration to the family earlier that year. Even after her husband Solomon Northup had regained his freedom, Anne Northup continued to work to support herself and her children for the rest of her life. She died in her late sixties or early seventies on August 8, 1876 in Moreau, New York 6.

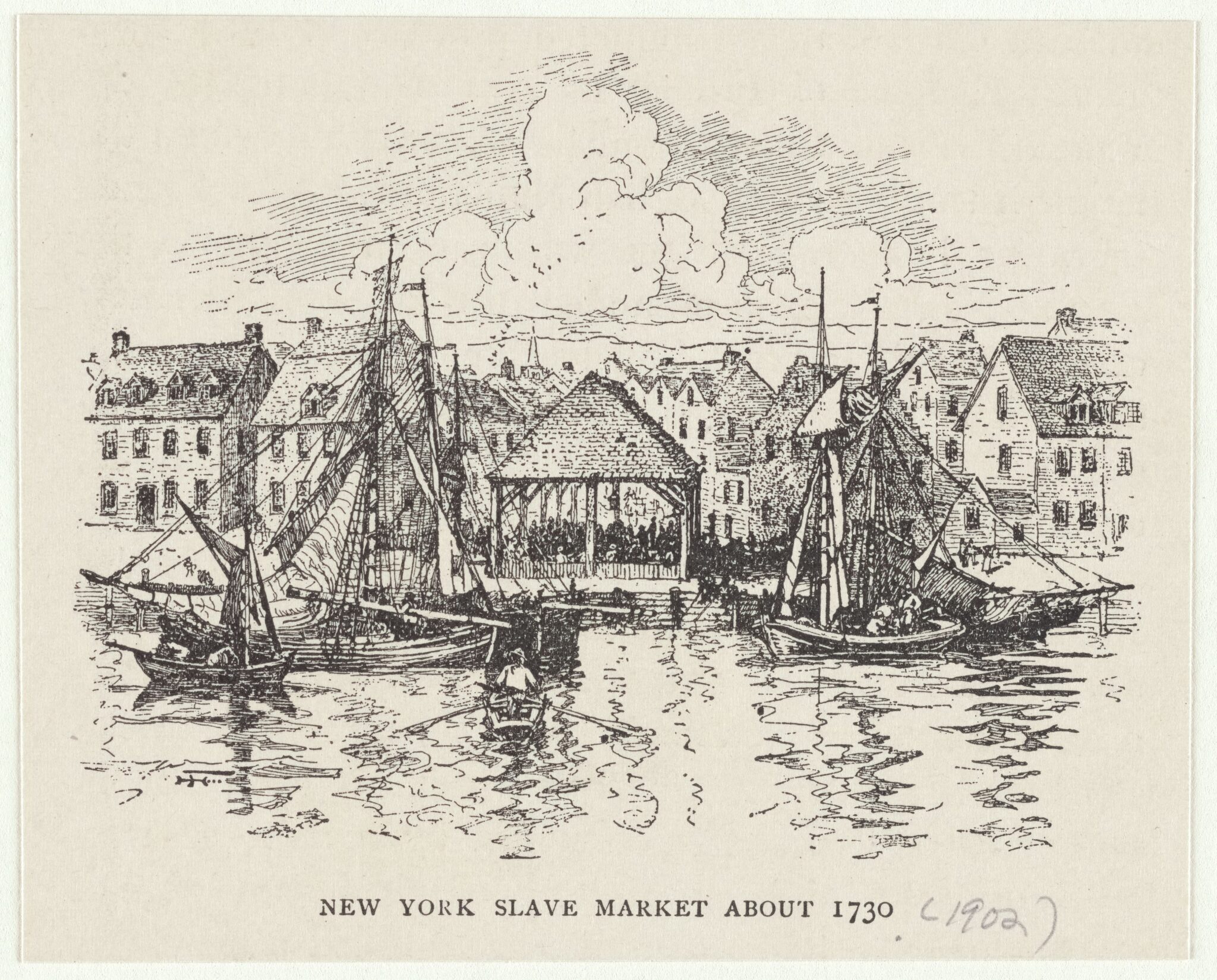

Harry Finn, New York slave market about 1730, 1902. Woodrow Wilson, From A history of the American people, New York : Harper, 1902-1903.

Uknown Persons (unknown)

It is believed that Roger Morris and Mary Philipse Morris oversaw the construction of the Morris-Jumel Mansion sometime between 1758 and 1765, however the actual laborers are unknown. We do know that enslaved labor was typically engaged for residential, commercial, and infrastructure construction projects during the colonial era. In New York, the first major infrastructure project, ordered by Governor Peter Stuyvesant in 1658, was the creation of a wagon road linking Harlem to New Amsterdam, where “Stuyvesant sent [Dutch West India] company slaves to work on the road 7.”

As the colonization of the island of Manhattan continued, many construction projects relied on the free labor of enslaved Africans and Native people, bolstering the wealth of the colonizers 8. Perpetuating the slave economy, colonists would frequently rent out enslaved individuals to each other colonizers for temporary forced labor projects, such as the construction of major infrastructure and buildings 9. After the British gained control of what was then known as Nieuw Amsterdam (now New York City) in 1664, the institution of slavery expanded in what became known as the city of New York, where eventually there were more enslaved Blacks than in any American city other than Charleston, South Carolina. A century later forty percent of New York households included enslaved people. Beyond this, New York’s merchants sold butter, cheese, cloth, candles, dishes, and flour to sugar plantations in the Caribbean, plantations dominated by enslaved labor. Rum and sugar grown and harvested by enslaved laborers in the Caribbean, working in brutal conditions, was sold in New York City markets.

One of these markets was the Meal Market, or “Slave Market,” located on the East River near what is now the south east corner of Wall and Water Streets in today’s lower Manhattan. Exchanging various commodities, this market was established through legislation in 1711 by the City Council as a centralized location to rent enslaved laborers for day work 10. For over fifty years, the Meal Market was a destination for tradesmen and craftsmen to purchase or rent out laborers as needed. Black laborers and artisans were highly skilled in the respective trades of their enslavers. Enslaved Black workers were commonly rented out at half the rate of free white laborers 11.

I well remember the arrival of the specie[money] to pay the French army, for the house was so crowded that day that my pastry room was used to lodge the specie

Hannah Till (ca. 1718-1826) & Isaac Till (unknown-1795)

During the Revolutionary War, George Washington and the Continental Army occupied various regions of today’s Greater New York City area. Traveling with the encampment were Hannah and Isaac Till, an enslaved married couple who were rented to Washington as cooks from their respective enslavers: New York Presbyterian minister Reverend John Mason and Continental Army Captain John Johnson of New Jersey. Hannah, who was of Oneida and African ancestry, was also named “Long Point” by her father.

According to Washington’s wartime expense book the Tills joined the general’s retinue, or service, in early July 1776. The Tills were skilled cooks. They were accustomed to laying multi-course meals with multiple dishes daily as Washington continued to eat in high style even while on campaign. In terms of provisioning the kitchen, the Tills would surely have been purchasing supplies from local farmers, hunters, and fishermen from the wilderness surrounding the Mansion, some of whom may have been Lenape.

The couple remained with the General throughout the War except for six months when Hannah worked for General Marquis de Lafayette, a French aristocrat and military officer who commanded American troops. In addition to rental fees, a portion of the Tills’ wages was paid directly to their enslavers to allow them to purchase their freedom. They were manumitted in October of 1778.

After the war ended, the Tills and their children settled in Philadelphia, where most of the African American population was free. One of their children, Isaac Worley Till, was born while the army was encamped at Valley Forge. In Philadelphia, the family worked as caterers, and remained connected with other formerly enslaved and free Black individuals, including Margaret Thomas, who became the wife of William Lee, George Washington’s enslaved valet. 12

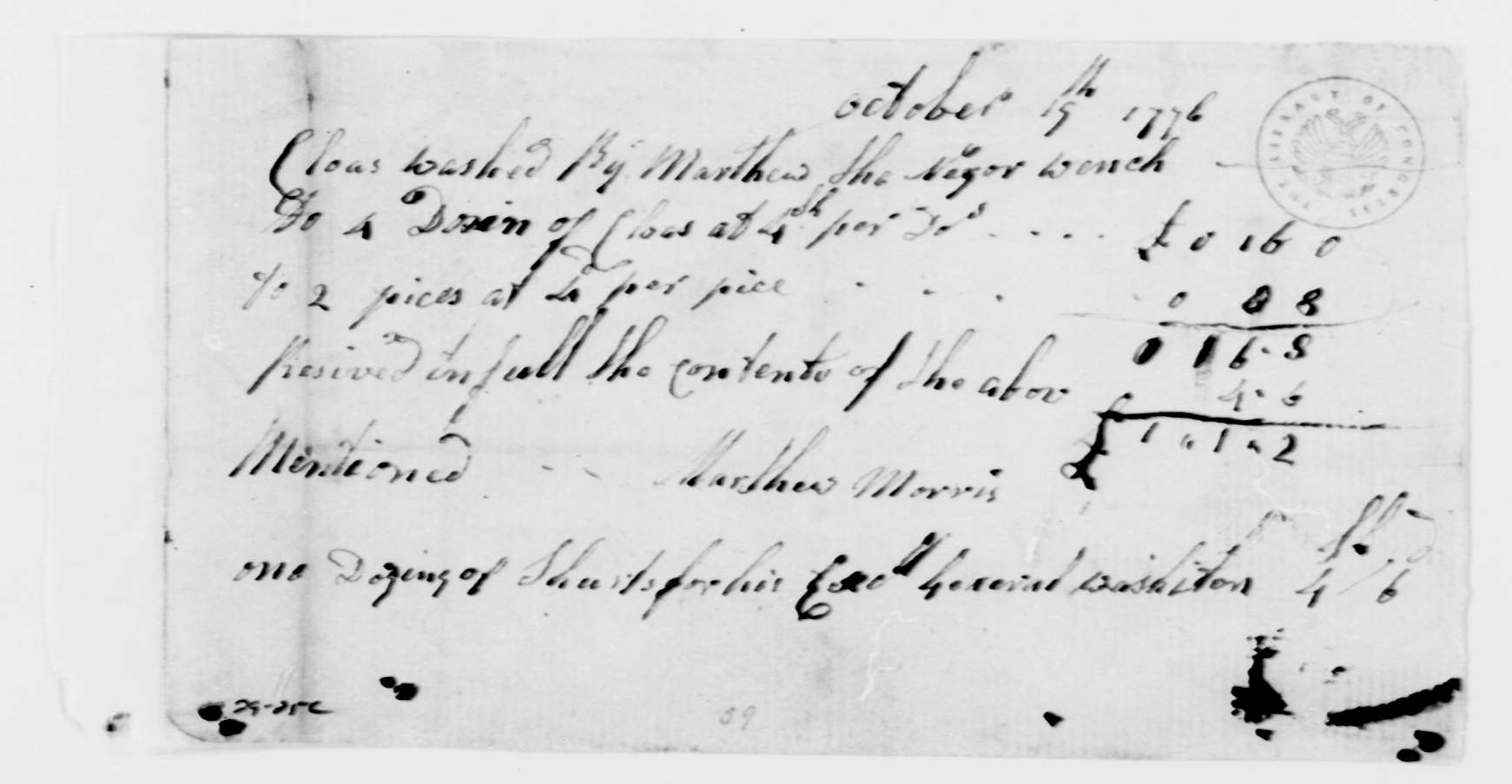

- George Washington Papers, Series 5, Financial Papers: Revolutionary War Vouchers and Receipted Accounts, 1776 -1780

Martha Morris (unknown)

The main piece of historical evidence about Martha Morris comes from a laundry receipt written on October 19, 1776 13. The receipt’s text reveals that a Black woman named Martha was paid to wash laundry at the Mansion for General George Washington, who was headquartered in the Mansion from September 15 – October 21, 1776. The existence of this laundry receipt and the use of the woman’s full name provide a rare and valuable glimpse into the lives of women of color in the Eighteenth Century.

Martha’s presence at the Mansion during the war, the payment for her services, and the reference to her surname as “Morris” provide important clues and raise additional questions about her life and status. Prior to the outbreak of war in 1775, the Mansion, known as Mount Morris, was a summer residence for the wealthy Loyalist Morris family. Some letters exchanged between Colonel Roger Morris and his wife, heiress Mary Philipse Morris, make reference to a woman named “Martha” among other individuals who work for the family, either as enslaved or indentured servants 14. Could this be the same Martha who laundered George Washington’s shirts? If so, perhaps she and other enslaved servants had been left behind by the Morris family to look after the house and its contents after Mary and the children fled the residence for Yonkers in the summer of 1776 15.

The Morris surname, combined with the references to a “Martha” in the Morris family letters, suggests that this woman may be the same individual. As was the case with Washington’s enslaved valet William Lee (who was originally enslaved by the Lee family of Virginia), Martha may have adopted her former enslavers’ surname in a common naming convention 16. Even if Martha of the Morris household and Martha Morris of Washington’s headquarters were one and the same we can’t even be certain of her status, given that the Morris family left the Mansion prior to Washington’s occupation of the house. The receipt is thought to have been written by Caleb Griggs, Washington’s enslaved, literate bodyguard and household account keeper.

Questions about Martha’s status as an enslaved, indentured, or free individual remain unanswered. Her service to the Washington camp may have provided welcome work during a chaotic and uncertain time in American history when lawlessness, inflation and a burgeoning black market made daily existence increasingly hard. Did the Morris Family abandon Martha or charge her with watching over the home after their evacuation? Was Martha paid for her services as a free woman or was payment sent to her enslaver if she was rented out to aid in running the household during Washington’s occupation 17? Although no additional documents referring to Martha Morris have yet emerged from the historic record, the fact that we know her name and of her existence is powerful, and serves as a reminder of the many unknown women of color whose names and stories were undocumented during the Revolution 18.

Across the street, carefully preserved as an historic site, is a colonial mansion that served as a headquarters for General George Washington

Paul Robeson (1898-1976)

Paul Robeson, born in Princeton, New Jersey in 1898, was a man of many talents: a successful stage and film actor, a concert singer known for his deep bass-baritone voice, a selected All-American athlete, a lawyer, and an outspoken political activist. After living and studying in Europe for several years in the 1930s, Robeson returned to the United States and moved to Harlem, where he had previously resided when he studied law at Columbia University. Robeson was well known during this era of his life for his roles on stage and in film, including productions of Othello and Show Boat.

Robeson resided at 555 Edgecombe Avenue from 1939 to 1941 with his wife, Eslanda Goode Robeson, – who was an author, anthropologist and photographer – their son Paul Jr., and his mother-in-law 19. The building, formerly known as the Roger Morris Apartments, initially opened in 1916 with an all-white policy, but after the building finally welcomed Black tenants in summer of 1939, the Robesons rented a penthouse and another apartment there that same fall. The building soon became predominantly Black, and famously home to a score of influential artists and thinkers, such as musicians Duke Ellington and Count Basie and boxer Joe Louis 20.

Robeson’s world travels expanded his social consciousness at home and abroad. He took his responsibility as a public figure seriously. He was recognized as a man steadfast in his principles: “The artist must elect to fight for freedom or slavery. I have made my choice. I had no alternative. The history of the capitalist era is characterized by the degradation of my people: despoiled of their lands, their true culture destroyed… denied equal protection of the law, and deprived of their rightful place in the respect of their fellows 21.” However, speaking his political mind came at a price. During the 1950s, during the notorious McCarthy Era of anti-Communist paranoia and accusations, Robeson was subjected to secret surveillance (ordered by Chief of the F.B.I., J Edgar Hoover), stripped of his passport, and blacklisted in the entertainment industry 22.

In 1953, Robeson returned to the Sugar Hill area of Harlem and lived in a townhouse at 16 Jumel Terrace, facing the Morris-Jumel Mansion. In his 1958 autobiography, Here I Stand (presumably written across the street), Robeson reflected upon the part his ancestors played in American history:

I am an American. From my window I gaze out upon a scene that reminds me how deep-going are the roots of my people in this land. Across the street, carefully preserved as an historic site, is a colonial mansion that served as a headquarters for General George Washington in 1776, during desperate and losing battles to hold New York against the advancing British. The winter of the following year found Washington and the ragged remnants of his troops encamped at Valley Forge, and among those who came to offer help in that desperate hour was my great-great-grandfather. He was Cyrus Bustill, who was born a slave in New Jersey and had managed to purchase his freedom. He became a baker and it is recorded that George Washington thanked him for supplying bread to the starving Revolutionary Army. 23

Robeson’s ancestor, Cyrus Bustill went on to become a prominent baker and brewer in Philadelphia where he was a founding member of that city’s Free African Society and an active abolitionist (6). Paul Robeson’s life and roots are a stark reminder that the American ideals of freedom and opportunity have been built on the oppression of Black people and other people of color over the past four hundred-plus years. After Robeson’s death in 1976, 555 Edgecombe was declared a National Historic Landmark in his honor. Edgecombe Avenue has also been co-named “Paul Robeson Boulevard”.

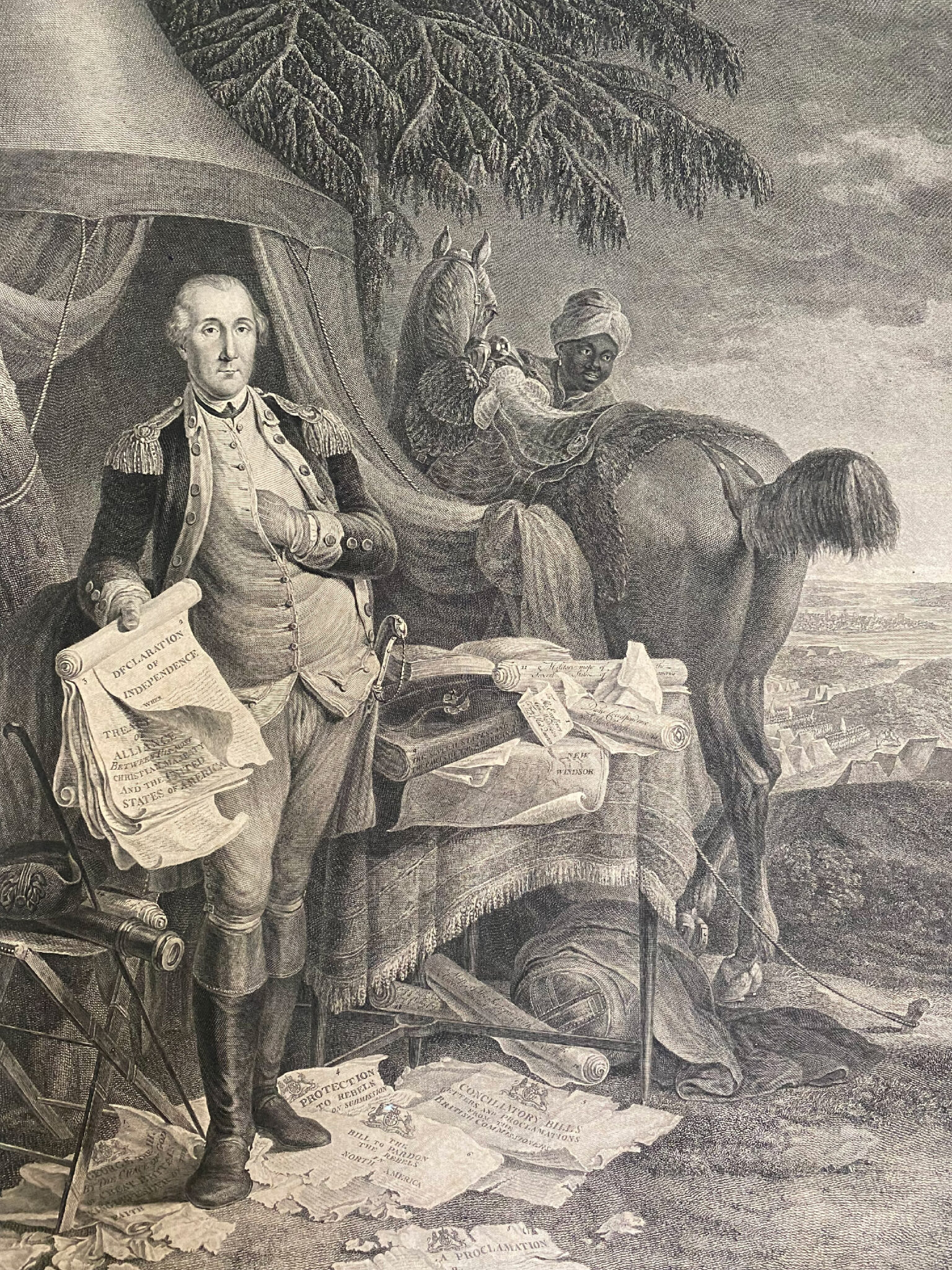

Noël Le Mire, Le Général Washington ne quid detrimenti capiat res publica, 1780, lithograph

William Lee (ca. 1752-1810)

William Lee was a Black man enslaved by George Washington for over 20 years as his valet, or personal attendant. Lee traveled with the General during the American Revolution, carrying out duties such as organizing his personal papers (indicating that Lee was literate), keeping his spyglass, and helping Washington dress. William Lee was at the Mansion from September 15 – October 21, 1776, the fall when General George Washington used the house as his military headquarters 24.

Little is known about where William Lee was born or grew up. In 1768, when he was about 15 or 16, George Washington purchased him and his brother Frank from a woman named Mary Lee in Virginia for £61.15 shillings, an extremely modest sum. William Lee was an excellent horseman and accompanied Washington on trips, fox hunts and rode alongside Washington during the entire Revolutionary War. He was a constant presence in Washington’s life and an active participant in the Continental Army’s milestones through the Revolutionary War as Washington’s de facto aide de camp, or secretary.

Due to his proximity and relationship with Washington, William Lee had a higher status within the enslaved community, with privileges available to him that were denied to others who were owned by the Washington family. When he met and wanted to marry a free Black woman named Margaret Thomas during the war, he was obliged to obtain permission from Washington. In a 1784 letter from Washington to Clement Biddle (Commissary General at Valley Forge under George Washington), Washington stated that William Lee could wed “if it can be complied with on reasonable terms as he has lived with me so long and followed my fortunes with fidelity 25.” Margaret Thomas, who had worked as a washerwoman and seamstress for Washington, may have also been at the Mansion in 1776 serving as housekeeper after the previous housekeeper—a free White woman—absconded Washington’s service following the Hickey Affair, the assassination attempt of Washington.

After a series of accidents in the 1780s left him unable to physically continue his role as Washington’s valet, William Lee was fitted with leg braces and continued to live at Mount Vernon as a shoemaker 26. Why was he granted such allowances? Washington believed that the two of them shared a close bond, writing in his will that Lee would be freed “as a testimony of my sense of his attachment to me, and for his faithful services during the Revolutionary War 27.” Lee was the only one of the 123 enslaved people owned by Washington who was immediately freed at Washington’s death while the remaining 122 were to be freed, or manumitted, following the death of his wife Martha 28. Whether William Lee felt the same about Washington is unknown. Though free, Lee remained at Mount Vernon, until his own death in 1810. Scholars indicate that he stayed at the estate due to his family connections and that his disabilities made it difficult for him to travel and work. William Lee is believed to be buried at Mount Vernon, in an unmarked grave amongst the estate’s formerly enslaved people. 29

Shop and Warehouse of Duncan Phyfe, 168–172 Fulton Street, New York City, 1817-1820

Unknown Persons (unknown)

Many fine and decorative arts pieces from the mid-nineteenth century were made from mahogany, a material known for its sleek, exotic look, but one with ties to exploitation and the international slave trade.

Many of the furniture objects throughout the Morris-Jumel Mansion are crafted from mahogany wood. Mahogany was a popular choice for furnishings for wealthy European and American elites in the eighteenth century due to the material’s durability and sleek, exoticized look once polished. Among the many furnishings in the Mansion’s collection made out of mahogany is a card table (or gaming table) crafted by prominent nineteenth century New York cabinetmaker, Duncan Phyfe (1768 – 1854). Historical documents confirm that Phyfe purchased mahogany from St. Domingo (today’s Haiti and Dominican Republic) to craft pieces, such as this table.

The history behind mahogany, its logging, and trade is rooted in colonization, environmental exploitation, and the Trans-Atlantic slave trade. The hardwood, native to the West Indies and the Bay of Honduras, had been used for centuries by local indigenous peoples to craft canoes and other utilitarian objects. During the eighteenth century, Spanish and English colonists found the West Indies species of mahogany desirable for furniture making and began harvesting the wood at an unsustainable rate. Within a few decades French and British colonizers had depleted the mahogany reserves of several islands in the Caribbean Sea.

The harvesting of mahogany required specialized knowledge of the tree, the land, and logging practices, and was quite labor intensive. Enslaved African people were forced to familiarize themselves with the requisite knowledge to harvest mahogany. Paradoxically, this knowledge of the tree and the trade empowered enslaved persons to hone their accrued knowledge and skills in defiance of their enslavers. This ranged from selling small pieces of the wood or other natural resources in local markets to selling entire logs of mahogany to their enslaver’s competition. However, by the early nineteenth century, the decrease in mahogany in the West Indies directly correlated to the increase in sugar plantations, which caused a greater need for more enslaved workers and cemented the shift toward a long term plantation economy. 30

She would transform from a trusted house slave for the most powerful American family to a criminal, guilty of stealing her own body away from her owners.

Ona Judge (1773-1848)

Ona Judge was born into slavery on January 1, 1773, on George Washington’s estate, Mount Vernon, in Virginia. From the age of twelve until adulthood, she served as Martha Washington’s personal attendant. Ona Judge would have attended to Martha Washington by helping her get dressed, emptying chamber pots, and by performing other daily domestic duties for Martha. In this capacity she likely spent time at the Morris-Jumel Mansion when George and Martha Washington, and members of the future presidential cabinet and their spouses, visited the Mansion for a celebratory dinner in 1790. When the house served as a residence, this room would have been the largest bedchamber; during the 1790 dinner, guests likely used this space as a private toilet, dressing room, resting area, and powder room.

During Washington’s eight years as president, his family, and several enslaved servants, including Ona Judge, lived in New York, the nation’s first capital, and then moved to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania when the capital was transferred there. Pennsylvania law stated that any enslaved person who had resided in the state for six months or more would earn the right to manumission, or freedom from enslavement. Washington expended great time and effort to circumvent this law. In a 1791 letter to his executive secretary, Tobias Lear, the President outlined his plans to send the enslaved individuals on trips back and forth between the new capital and Mount Vernon before the required six months had elapsed. By intentionally trafficking them across state lines, each time effectively resetting their six month period in the state, the Washingtons demonstrated their commitment to maintaining the system of slavery. However, this tactic did not necessarily prevent his enslaved servants from discovering the Pennsylvania law.

When Ona Judge learned that she was to be transferred to George and Martha’s granddaughter, Elizabeth Parke Custis, upon Custis’ marriage, she planned her self-emancipation mobilizing a network of enslaved workers and free Black and White abolitionists in order to flee. Likely she met Free Black individuals and groups during personal outings in Philadelphia, who later helped her to plan her journey. She eventually fled while the Washingtons were distracted during a long dinner, and boarded a ship run by Captain John Bolles to Portsmouth, New Hampshire.

Upon realizing that Ona Judge had escaped, Washington posted a runaway ad that described her skin color, features, stature, and listed a reward of $10. Though his hired slave catchers made several attempts to recapture her, Ona Judge always managed to evade them. While living in New Hampshire in 1845, Ona Judge recounted a confrontation she had with a slave catcher in a newspaper interview. He tried to convince her that, if she came back of her own free will, she would be freed upon her return to Mount Vernon. Unconvinced, she had simply responded, “I am free now and choose to remain so.” Ona Judge remained a free Black woman until her death in 1848.31

The essays associated with “Our Stories” were created by Morris-Jumel Mansion staff under the guidance of a group of community scholars: Cheyney McKnight, John Reddick, Eric K. Washington, and Kamau Ware. Assistance was also provided by Ramin Ganeshram. This project was made possible by a Humanities New York Action Grant and by support from the Knickerbocker Chapter of the National Society of the Daughters of the American Revolution. Any views, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed in this website do not necessarily represent those of the National Endowment for the Humanities.

References

Bibliography for Introduction: White, S. Somewhat More Independent: The End of Slavery in New York City (1991, University of Georgia Press); Harris, L.M. In the Shadow of Slavery: African Americans in New York City 1626-1863; Robertson, Stephen, Shane White, Stephen Garton, and Graham White, “This Harlem Life: Black Families and Everyday Life in the 1920s and 1930s.” Journal of Social History 44, no. 1 (2010): 97–122.

Solomon Northup, Twelve Years a Slave: Narrative of Solomon Northup, a Citizen of New-York, Kidnapped in Washington City in 1841, and Rescued in 1853. Introduction by Dolen Perkins-Valdez (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2013), 4; David Fiske Humanities NY lecture, “Anne Hampton Northup,” Morris-Jumel Mansion archives, October 6, 2020. Anne is frequently described as “mulatto” in Federal Census records, including the 1850 Census, New York State, Saratoga County, Town of Moreau.

The year of their marriage is disputed, with Solomon Northup claiming it was 1829 and Anne Northup testifying that it was 1828. Northup, Twelve Years a Slave. Introduction by Dolen Perkins-Valdez (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2013) 4-5, 285-7.3

David Fiske Humanities NY lecture, “Anne Hampton Northup,” Morris-Jumel Mansion archives, October 6, 2020.

David Fiske, Clifford W. Brown, and Rachel Seligman, Solomon Northup: The Complete Story of the Author of Twelve Years a Slave. (Santa Barbara, CA: Praeger, 2013), 159-163; U.S. Supreme Court, U.S. Supreme Court Transcript of Record Bowen v. Chase.5

David Fiske, Solomon Northup: His Life Before and After Slavery, 71; Obituary, Saratoga Sentinel, August 17, 1876.

Burrows, Edwin G., and Mike Wallace. Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898. 1st Edition. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2000.

White, S. Somewhat More Independent: The End of Slavery in New York City (1991, University of Georgia Press)

Burrows, Edwin G., and Mike Wallace. Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898. 1st Edition. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2000.

Law Appointing a Place for More Convenient Hiring of Slaves, Minutes of the Common Council of the City of New York, 1675-1776, Volume 4; https://www.wnyc.org/story/nyc-acknowledge-its-slave-market-more-50-years/

“Slavery in New York.” Accessed May 3, 2022. http://www.slaveryinnewyork.org/history.htm.

Washington, George. George Washington Papers, Series 5, Financial Papers: Revolutionary War Vouchers and Receipted Accounts, -1780. /1780, 1776. Manuscript/Mixed Material, quoted in “The Mystery of Hannah Till & Isaac” (unpublished manuscript); Watson, John Fanning. Annals of Philadelphia, being a collection of memoirs, anecdotes, and incidents of the city and its inhabitants, from the days of the Pilgrim founders (New York: E.L. Carey & A. Hart, 1830), 552; “From George Washington to Clement Biddle, 28 July 1784,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/04-02-02-0014. [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Confederation Series, vol. 2, 18 July 1784 – 18 May 1785, ed. W. W. Abbot. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1992, p. 14.]

“Matthew [sic] Morris to George Washington, October 19, 1776.” George Washington Papers, Series 5, Financial Papers: Revolutionary War Vouchers and Receipted Accounts,-1780. /1780, 1776. Manuscript/Mixed Material. https://www.loc.gov/item/mgw500029/.

Roger Morris to Mary Morris, Letter 16 (14 March 1776) & Letter 31 (2 March 1777). Transcribed letters from Colonel Roger Morris, Mount Morris, NY, to Mary Philipse Morris of Philipse Manor Hall in Yonkers,1775-1777. Morris-Jumel Mansion Archives.

Research indicates that it was common for families who traveled to different estates and plantations in different seasons would leave enslaved individuals and servants to take care of the property. Such was the case at the Van Cortlandt House.

Dr. Julie Miller, “George Washington’s Washing and the Women Who Did It,” History Hub CROWD, June 4, 2020, https://historyhub.history.gov/community/crowd-loc/blog/2020/06/29/george-washington-s-washing-and-the-women-who-did-it; Dr. Julie Miller, “History from Behind the Scenes: Martha Morris and George Washington,” Teaching with the Library of Congress, January 11, 2012, https://blogs.loc.gov/teachers/2012/01/experiencing-history-from-behind-the-scenes-martha-morris-and-george-washington/; Jim Ambuske and Dr. Julie Miller, “193: Rifling Through Washington’s Receipts,” January 21, 2021, in Conversations at the Washington Library, produced by the Center for Digital History (CDH) at the Fred W. Smith National Library for the Study of George Washington at Mount Vernon, podcast, MP3 audio, https://www.georgewashingtonpodcast.com/show/conversations/193-rifling-through-washingtons-receipts-with-dr-julie-miller/

Kristin L. Gallas. "Interpreting Slavery with Children and Teens at Museums and Historic Sites," Interpreting History Series, ed. Rebecca K. Shrum (London: Rowman & Littlefield, 2021), 21.

“George Washington Papers, Series 5, Financial Papers: Revolutionary War Vouchers and Receipted Accounts, 1776 -1780.” Accessed May 3, 2022. https://crowd.loc.gov/campaigns/ordinary-lives-in-george-washingtons-papers-the-revolutionary-war/revolutionary-war-receipts-1776-1780/mgw500029/mgw500029-117/.

United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service. National Register of Historic Places – Nomination Form: Paul Robeson Residence. Prepared by Lynne Gomez-Graves. https://npgallery.nps.gov/NRHP/GetAsset/NHLS/76001248_text

Gray, Christopher. “Streetscapes/409 Edgecombe Avenue; An Address That Drew the City’s Black Elite.” The New York Times, July 24, 1994, sec. Real Estate. https://www.nytimes.com/1994/07/24/realestate/streetscapes-409-edgecombe-avenue-an-address-that-drew-the-city-s-black-elite.html.

Robeson, Susan. The Whole World in His Hands: A Pictorial Biography of Paul Robeson. 60. Citadel Press, 1981.

While We Are Still Here. “Our History Continues In Harlem.” While We Are Still Here. Accessed May 3, 2022. https://whilewearestillhere.org/william-%22count%22-basie.

Robeson, Paul. Here I Stand. Beacon Press, 1998.

Winch, Julie (2000). The Elite of Our People: Joseph Willson's Sketches of Black Upper-Class Life in Antebellum Philadelphia. The Penn State University Press

According to Associate Curator Jessie MacLeod at George Washington’s Mount Vernon, it is a “safe assumption” that Lee was also onsite at the Mansion with Washington in the fall of 1776, see Jessie MacLeod HumanitiesNY lecture, “William Lee,” Morris-Jumel Mansion archives, September 22, 2020.

George Washington to Clement Biddle, July 28, 1784, Founders Online, National Archives. [Original source: Papers of George Washington.]

Jessie MacLeod, “William (Billy) Lee,” Digital Encyclopedia, George Washington’s Mount Vernon.

George Washington’s Diary, Apr. 22, 1785; Mar. 1, 1788, Founders Online, National Archives. [Original source: Papers of George Washington.]

George Washington’s Last Will and Testament, 9 July 1799,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/06-04-02-0404-0001. [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Retirement Series, vol. 4, 20 April 1799 – 13 December 1799, ed. W. W. Abbot. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1999, pp. 479–511.]

Anderson, Jennifer L. Mahogany. Harvard University Press, 2012.; Earle, Carville V. “A Staple Interpretation of Slavery and Free Labor.” Geographical Review 68, no. 1 (January 1978): 51–65; Ruef, Martin. “Constructing Labor Markets: The Valuation of Black Labor in the U.S. South, 1831 to 1867.” American Sociological Review 77, no. 6 (2012): 970–98.; Kane, Patricia E. “Mahogany: New Research on the Wood of Choice in Early Rhode Island Furniture.” Yale University Art Gallery Bulletin, 2019, 69–77. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26899730.; Revels, Craig S. “Concessions, Conflict, and the Rebirth of the Honduran Mahogany Trade.” Journal of Latin American Geography 2, no. 1 (2003): 1–17. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25765044.; Stevenson, Neil S. “Silvicultural Treatment of Mahogany Forests in British Honduras." Empire Forestry Journal 6, no. 2 (1927): 219–27. http://www.jstor.org/stable/42591669.; “The Mahogany Trade of Honduras.” Science 17, no. 418 (1891): 79–80. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1765838.; “The Mahogany Industry of Honduras.” Journal of the Royal Society of Arts 60, no. 3102 (1912): 604–604. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41340143.; “Mahogany Cutting in Honduras.” Scientific American 23, no. 20 (1870): 310–310. http://www.jstor.org/stable/26033404.; Cornelius, Charles Over. “Furniture From the Workshop of Duncan Phyfe.” The American Magazine of Art 13, no. 12 (1922): 521–28. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23939043.; R. T. Haines Halsey, and Charles O. Cornelius. “An Exhibition of Furniture from the Workshop of Duncan Phyfe.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin 17, no. 10 (1922): 207–14. https://doi.org/10.2307/3254300.; Carson, Marian S. “‘The Duncan Phyfe Shops’ by John Rubens Smith, Artist and Drawing Master.” American Art Journal 11, no. 4 (1979): 69–78. https://doi.org/10.2307/1594180.; Jones, Edward V. “Charles-Honoré Lannuier and Duncan Phyfe, Two Creative Geniuses of Federal New York.” American Art Journal 9, no. 1 (1977): 4–14. https://doi.org/10.2307/1594051.; Winterthur Museum, Garden & Library. “Finding Aids,” February 23, 2021. https://www.winterthur.org/finding-aids/.

Bibliography for Ona Judge: Based on Pennsylvania’s An Act for the Gradual Abolition of Slavery 1780, which then included a 1788 amendment that prohibited rotating out enslaved persons. This law, however, did not apply to federal officials like Washington and no legal institution or other institution challenged George Washington’s practices.; Dunbar, Erica Armstrong, and Kathleen Van Cleve. Never Caught, the Story of Ona Judge: George and Martha Washington’s Courageous Slave Who Dared to Run Away; Young Readers Edition. Simon and Schuster, 2019.; Letters and Recollections of George Washington: Being Letters to Tobias Lear and others between 1790 and 1799, showing the First American in the management of his estate and domestic affairs. With a diary of Washington’s last days, kept by Mr. Lear. New York, 1906. 37–39.; Chase, Benjamin. “A Slave of George Washington.” The Liberator. January 1, 1847, 1 edition.; Adams, Rev. T.H. “Washington’s Runaway Slave, and How Portsmouth Freed Her.” The Granite Freeman. May 22, 1845.; “Advertisement for the Capture of Oney Judge, Philadelphia Gazette (May 24, 1796) – Encyclopedia Virginia.” Accessed May 3, 2022: https://encyclopediavirginia.org/entries/advertisement-for-the-capture-of-oney-judge-philadelphia-gazette-may-24-1796/.; LaRoche, Cheryl Janifer, and Darlene Clark Hine. “Coerced but Not Subdued: The Gendered Resistance of Women Escaping Slavery.” Gendered Resistance: Women, Slavery, and the Legacy of Margaret Garner, edited by Mary E. Frederickson and Delores M. Walters, 49–76. University of Illinois Press, 2013. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5406/j.ctt3fh57q.8.; Furstenberg, François. “Atlantic Slavery, Atlantic Freedom: George Washington, Slavery, and Transatlantic Abolitionist Networks.” The William and Mary Quarterly 68, no. 2 (2011): 247–86. https://doi.org/10.5309/willmaryquar.68.2.0247.; Frey, Sylvia R. “Between Slavery and Freedom: Virginia Blacks in the American Revolution.” The Journal of Southern History 49, no. 3 (1983): 375–98. https://doi.org/10.2307/2208101.; Berry, Daina Ramey. “‘In Pressing Need of Cash’: Gender, Skill, and Family Persistence in the Domestic Slave Trade.” The Journal of African American History 92, no. 1 (2007): 22–36. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20064152.