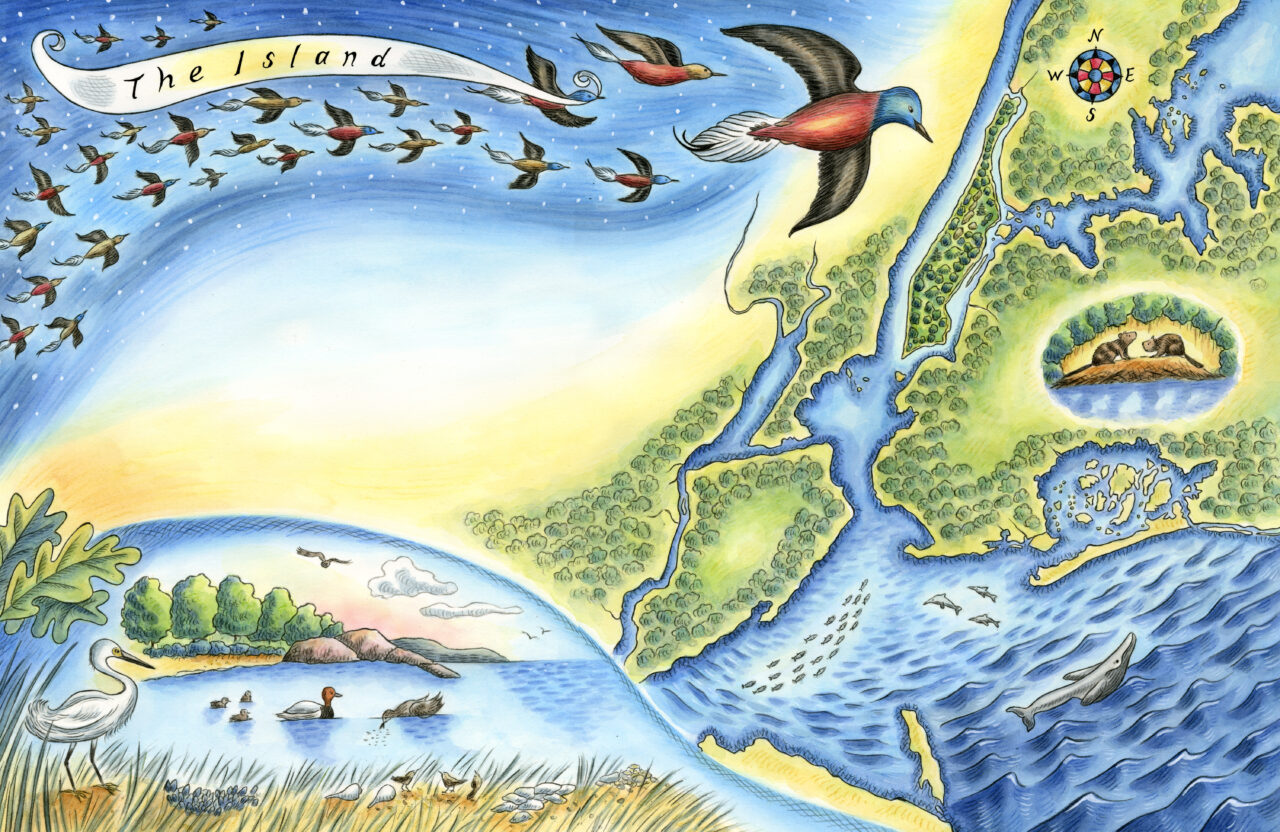

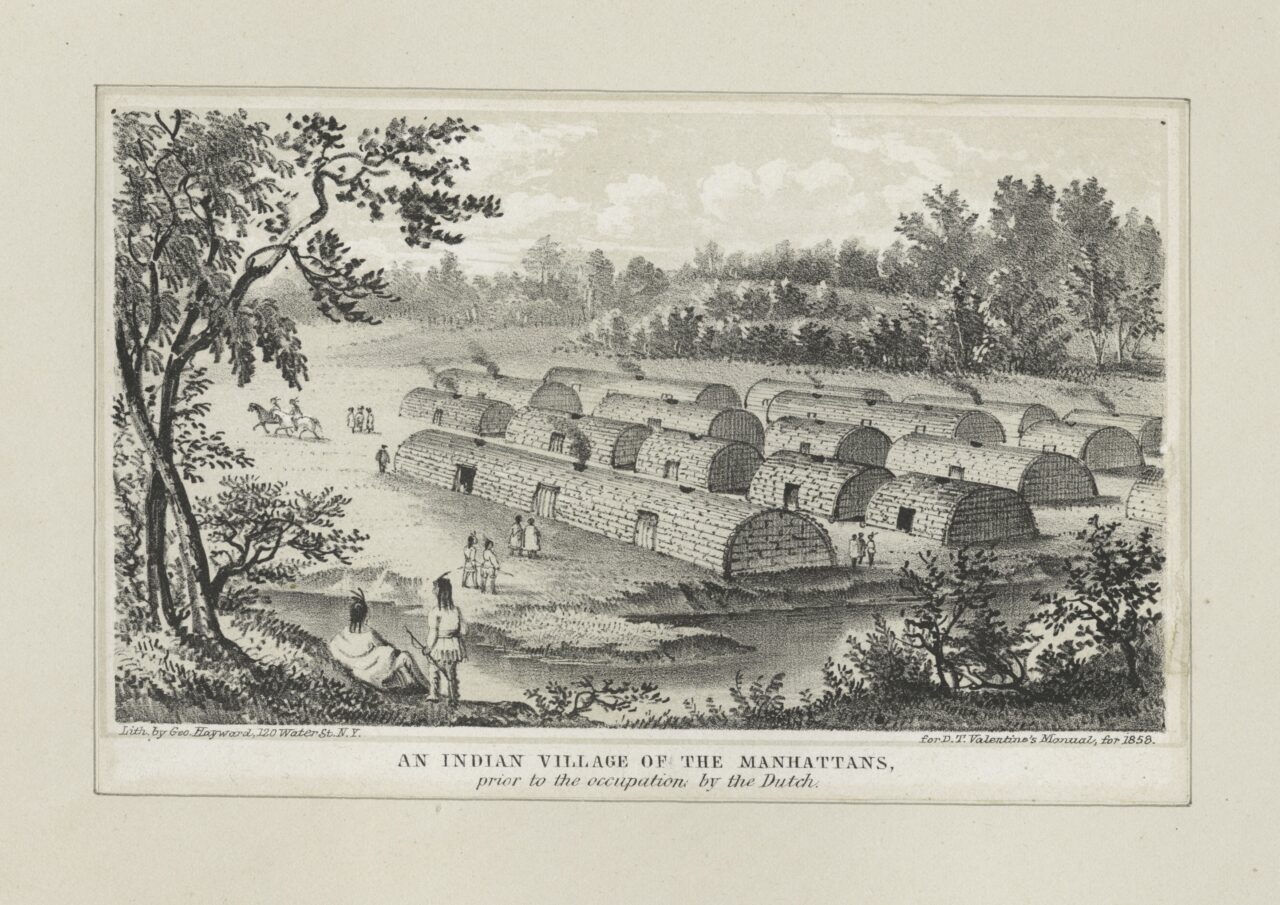

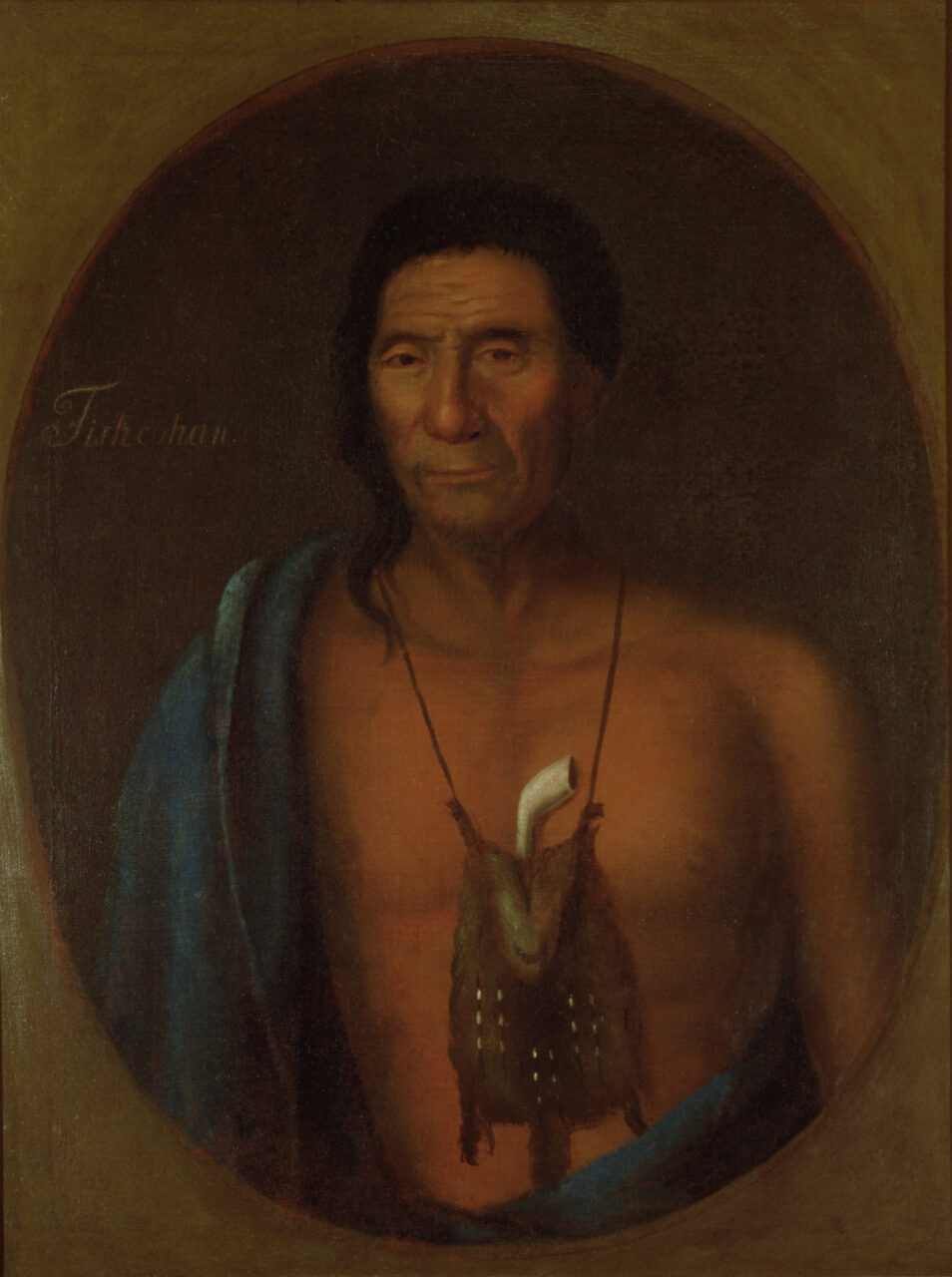

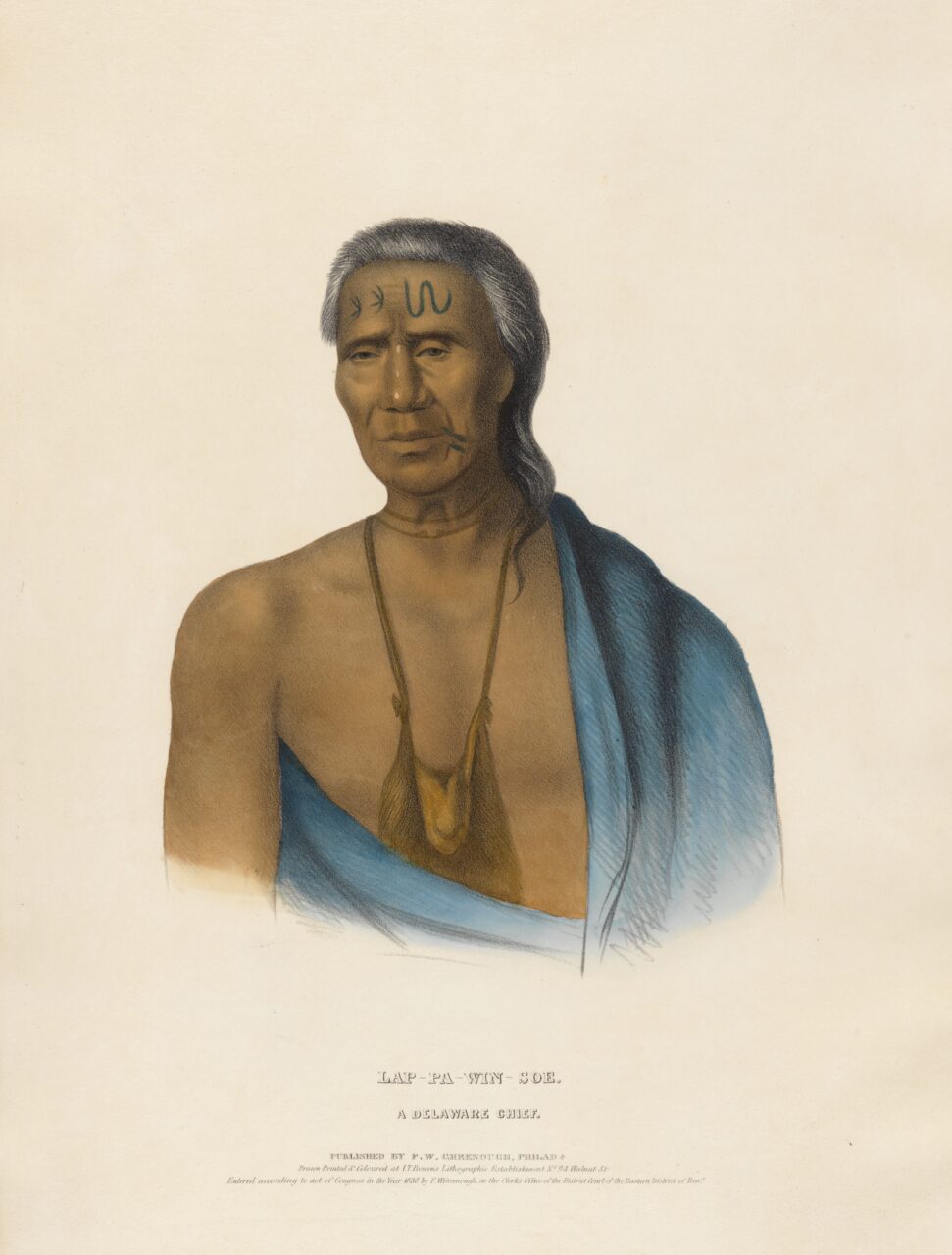

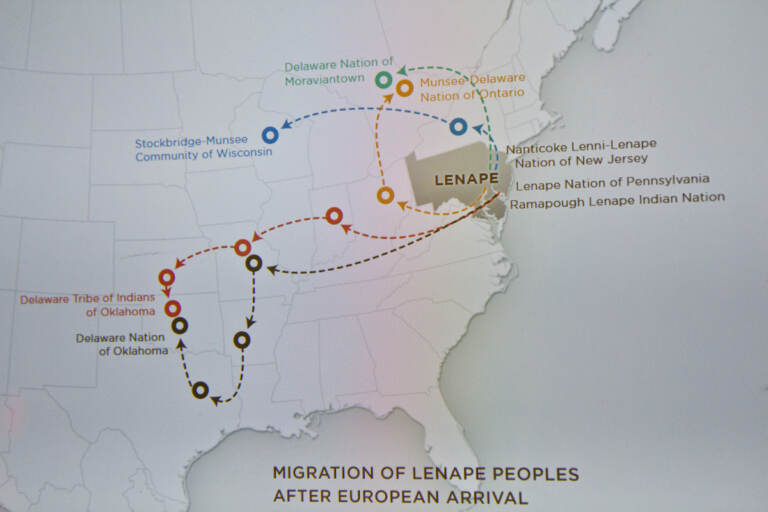

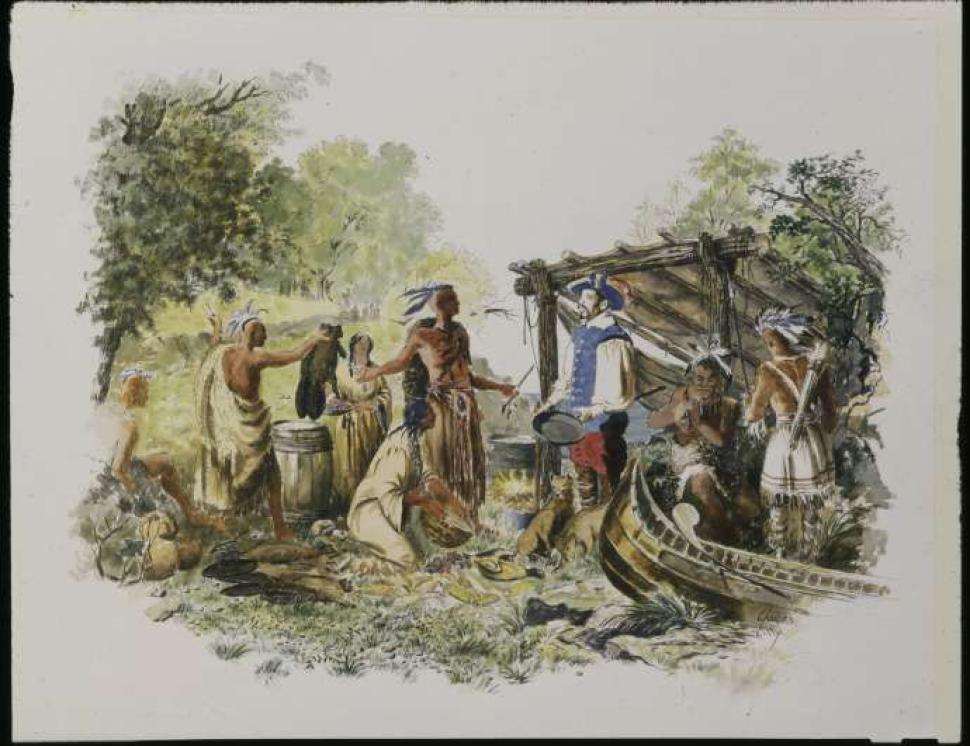

Throughout the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, both Dutch and British colonizers used propaganda to lure settlers to Manhattan Island with the promise of better lives. During the early years of Dutch occupation, many Dutch citizens had little interest in leaving an economically prosperous Netherlands for the Colony of New Netherland. Once established, settlers began exploiting indigenous communities, exhausting the island’s fertile resources, and developing infrastructure and systems to provide and build wealth for themselves.

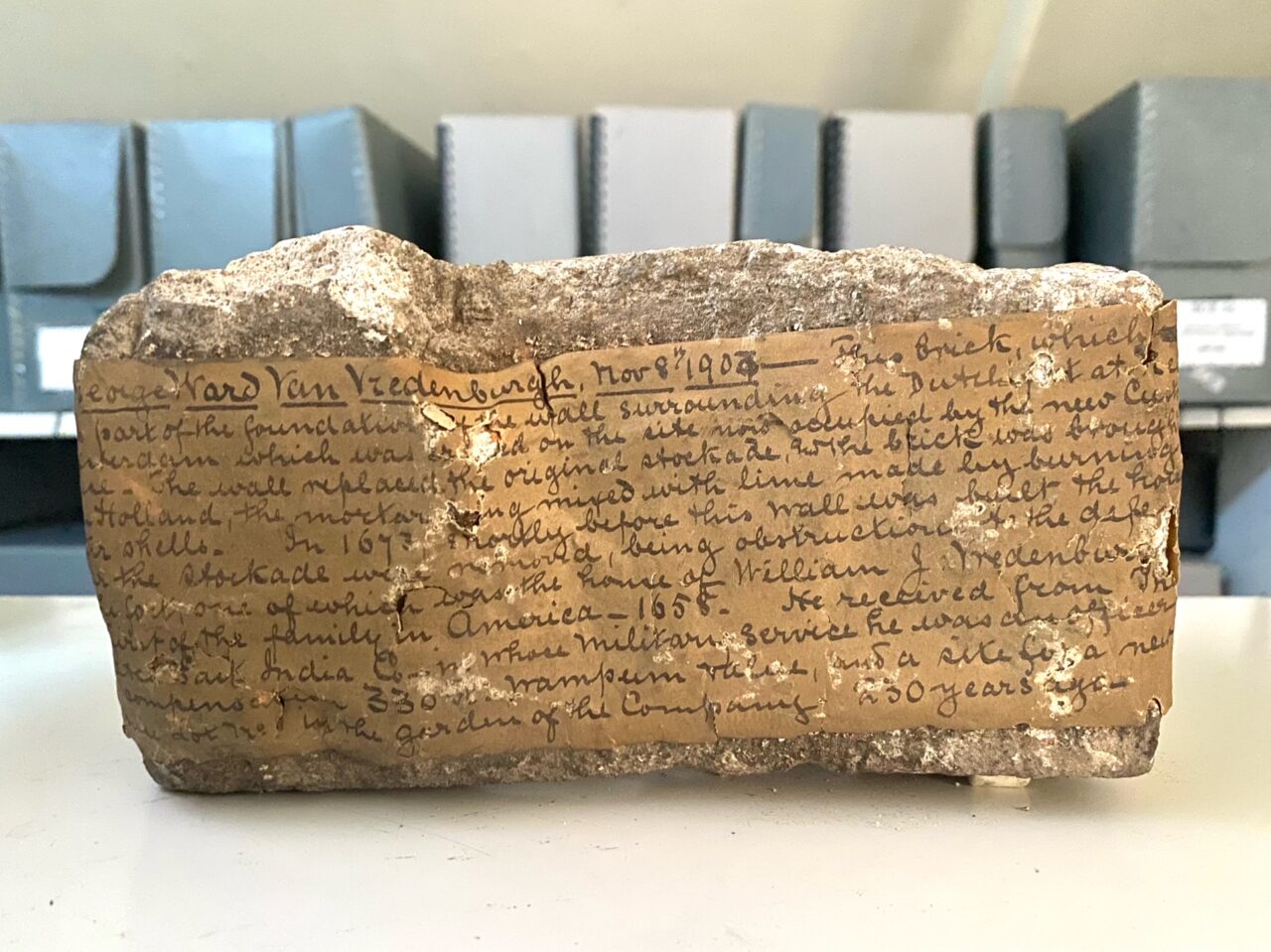

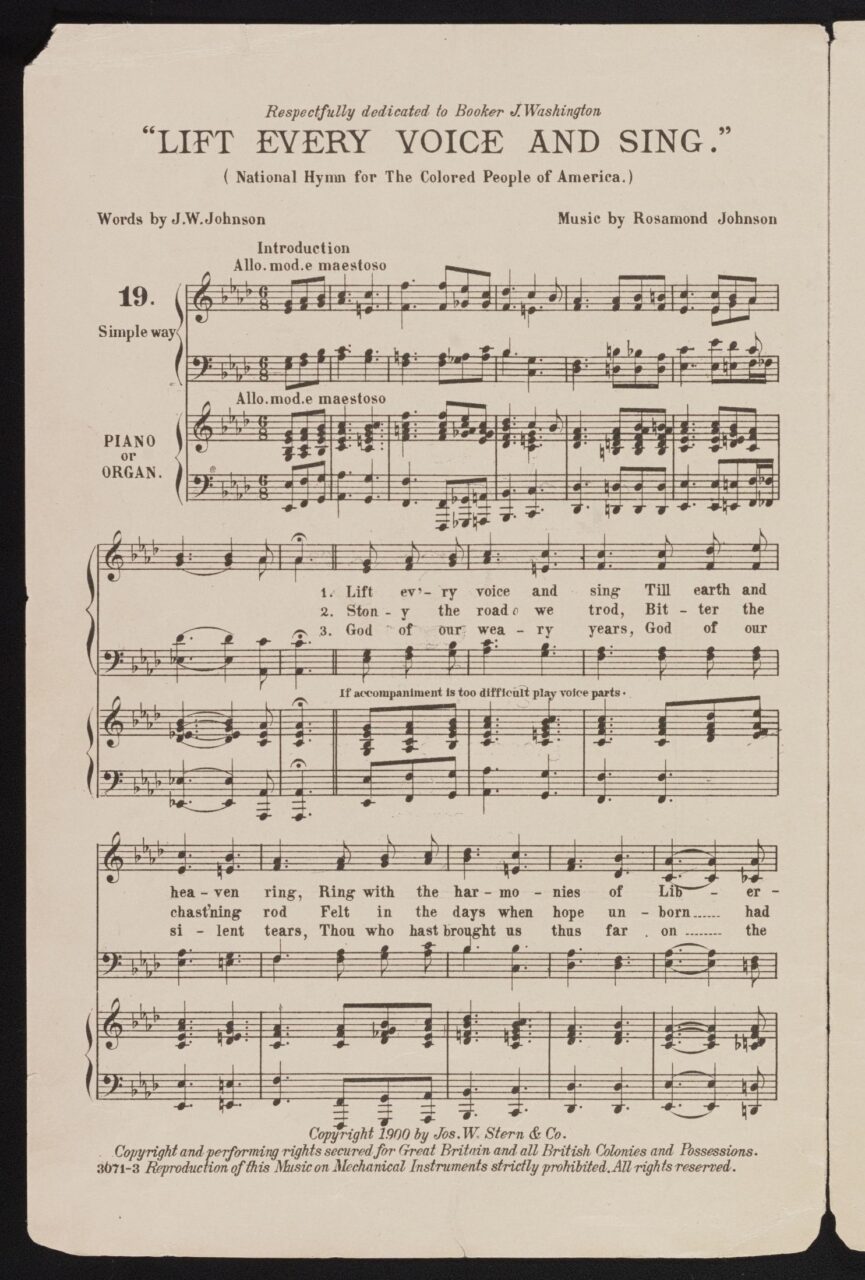

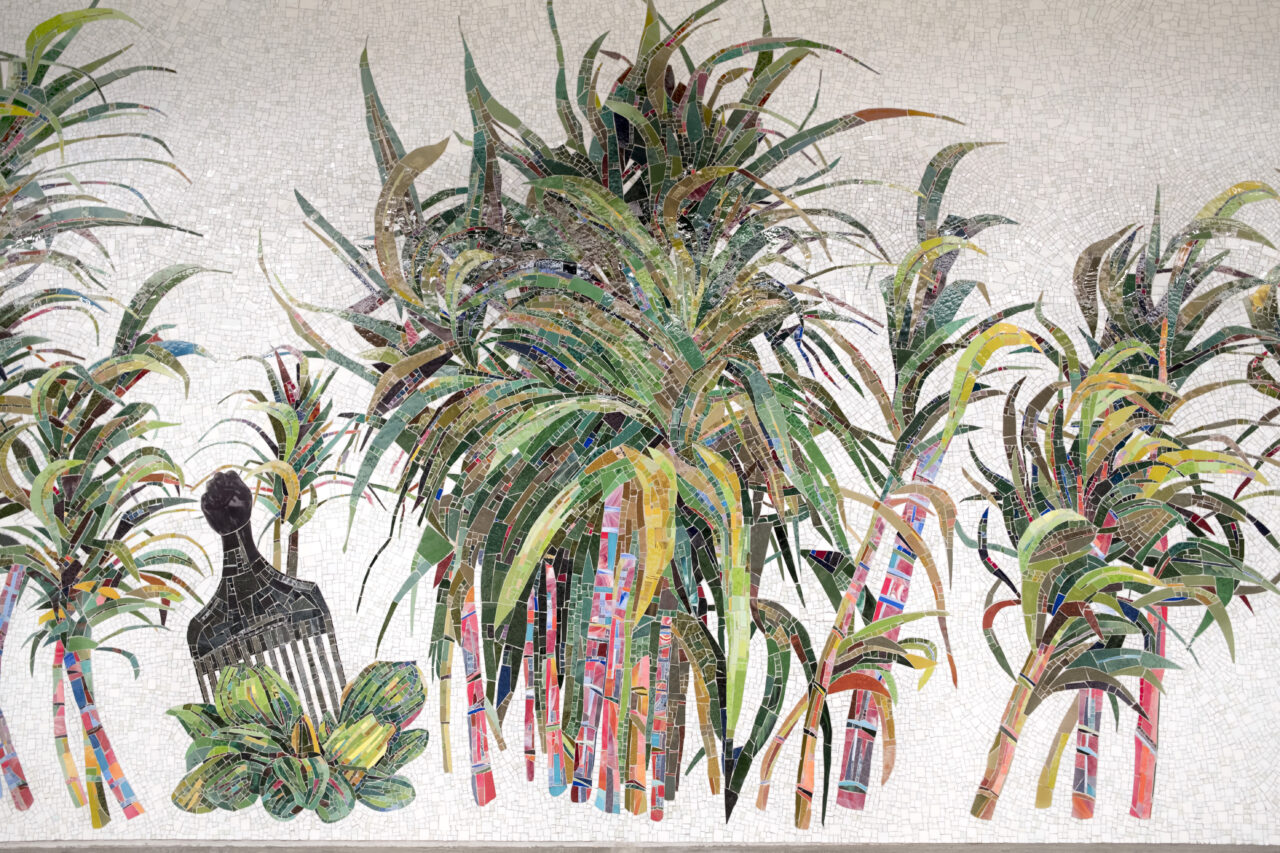

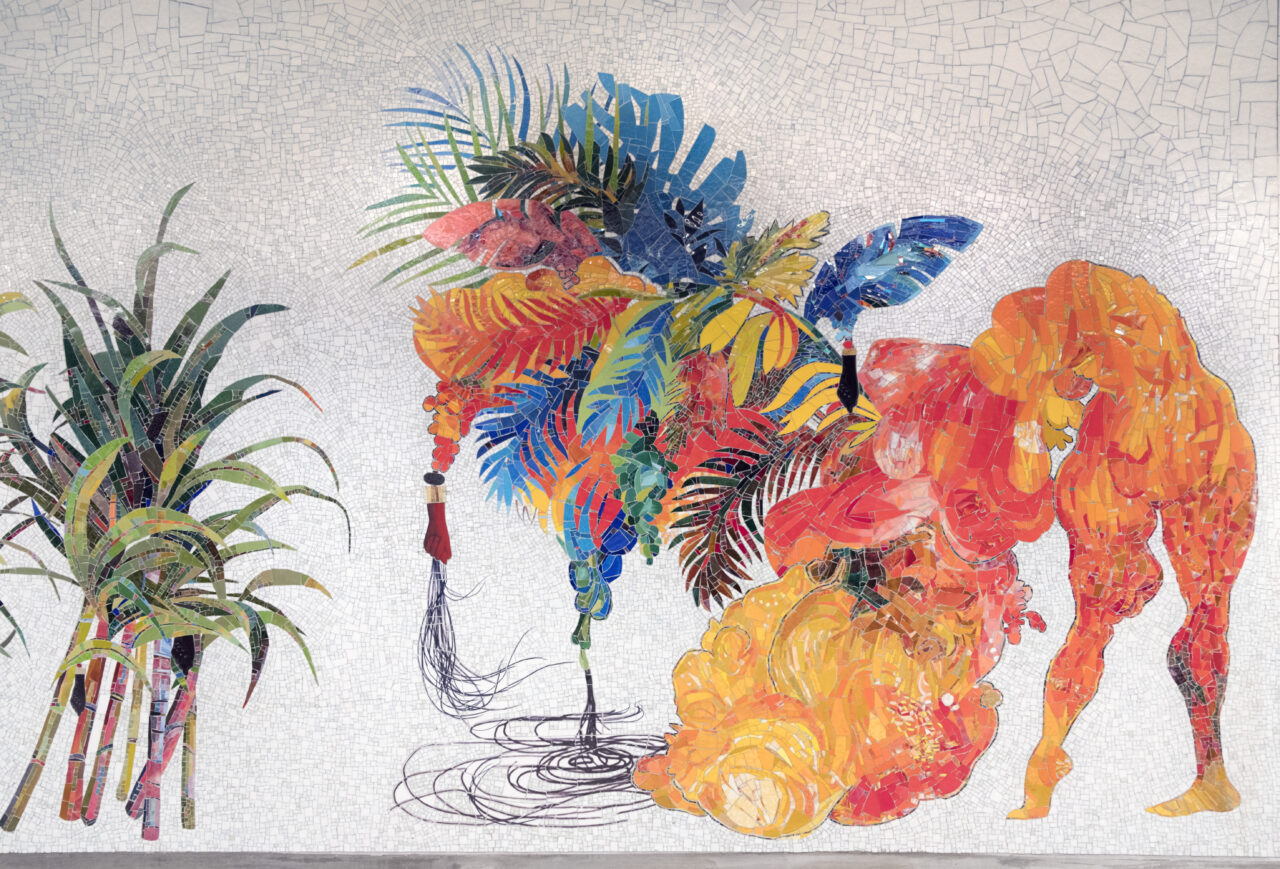

In 1626, the first African enslaved individuals, 11 in total, arrived in New Amsterdam,and were bought from pirates who stole Spanish ships. By 1644, Africans were being brought directly to New Amsterdam from Africa. In 1658 Peter Stuyvesant ordered the colony’s enslaved Africans to build a wagon road from the New Amsterdam settlement in Lower Manhattan to the newly incorporated settlement of New Harlem in Upper Manhattan. Under the administration of the Dutch West Indies Company, enslaved Africans and white indentured servants were considered a single social class, and were subject to the same restrictions regarding personal freedom, and property ownership limits. This combined class was allowed to come and go freely, and many eventually bought their own freedom and were allowed to purchase marshy plots of land in lower Manhattan for their farms. By 1664, when rule of the Dutch colony was ceded to the English, 174 enslaved men and 132 enslaved women had arrived. Two years later, there were thirty documented Black property owners in the region while New York boasted the biggest slave market in North America, located on Wall Street.

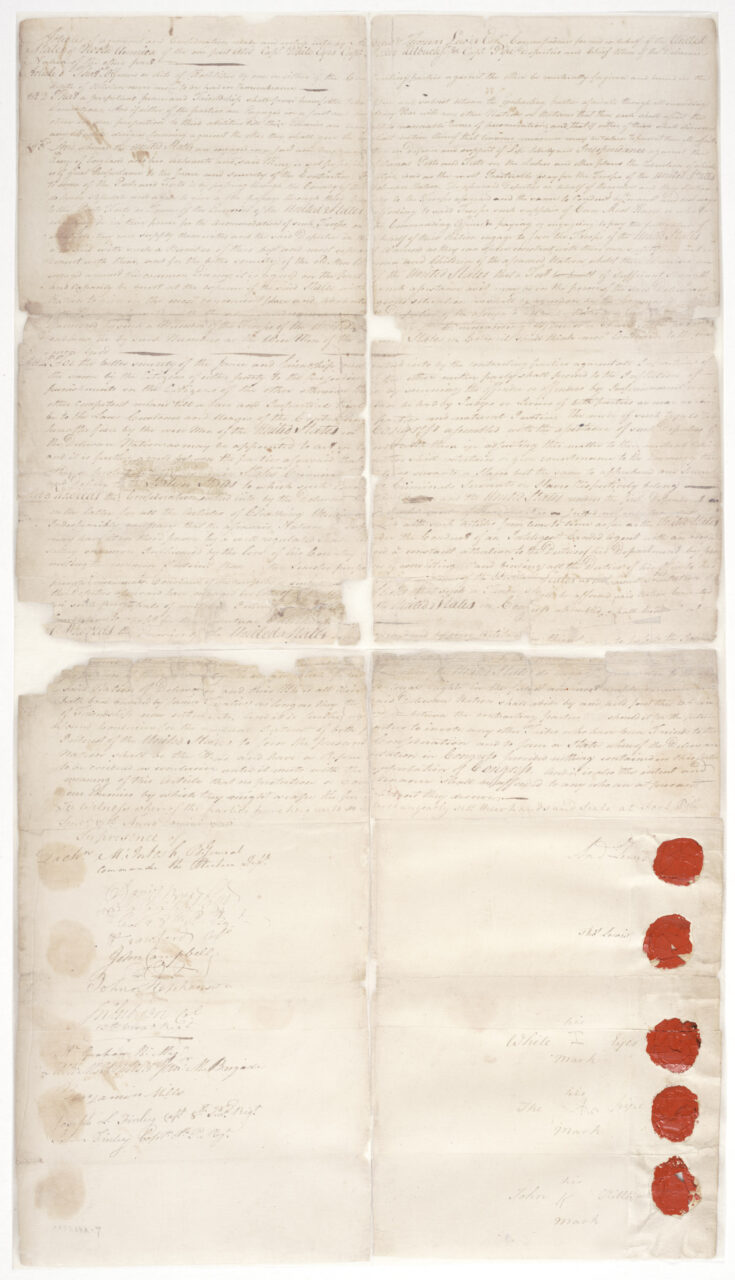

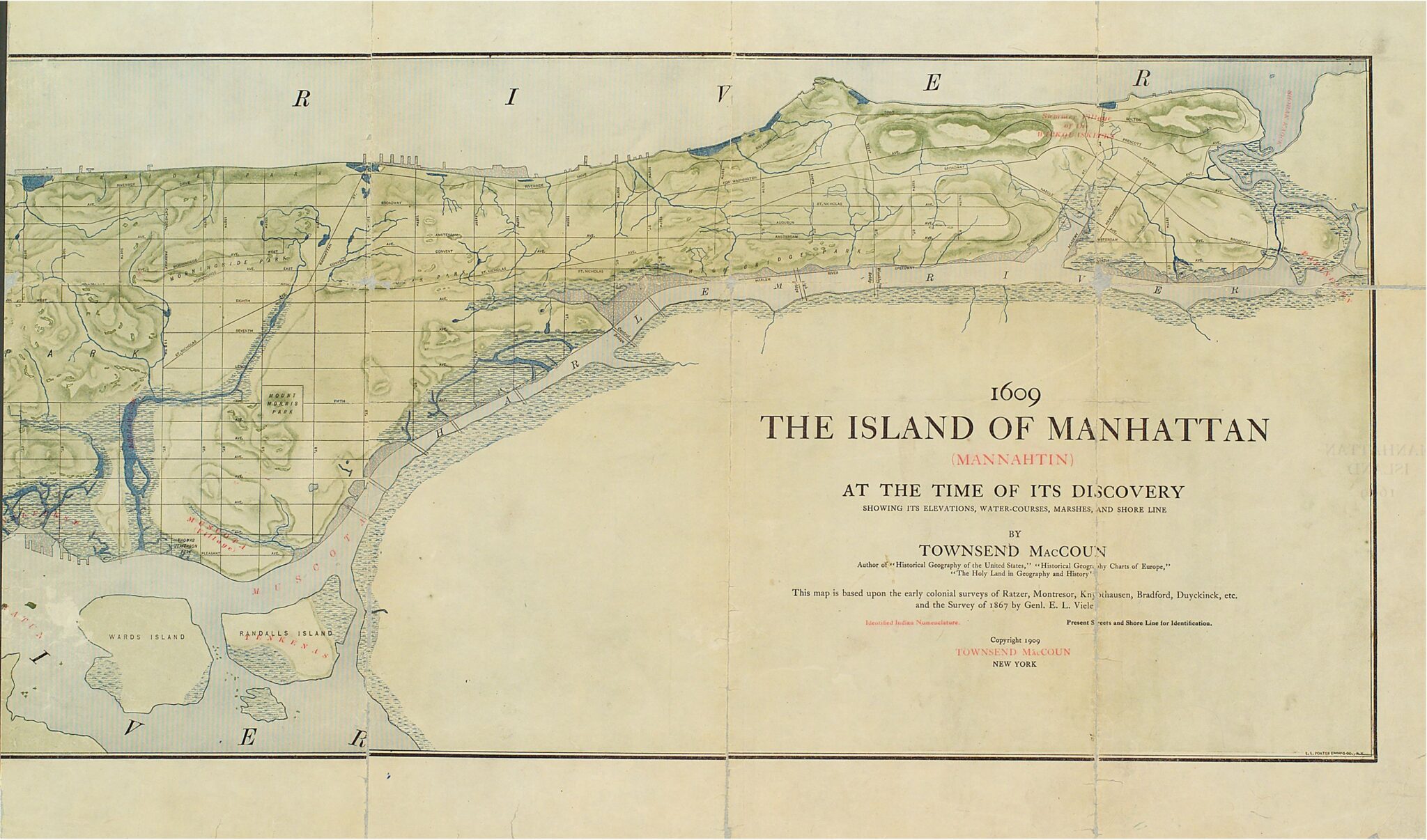

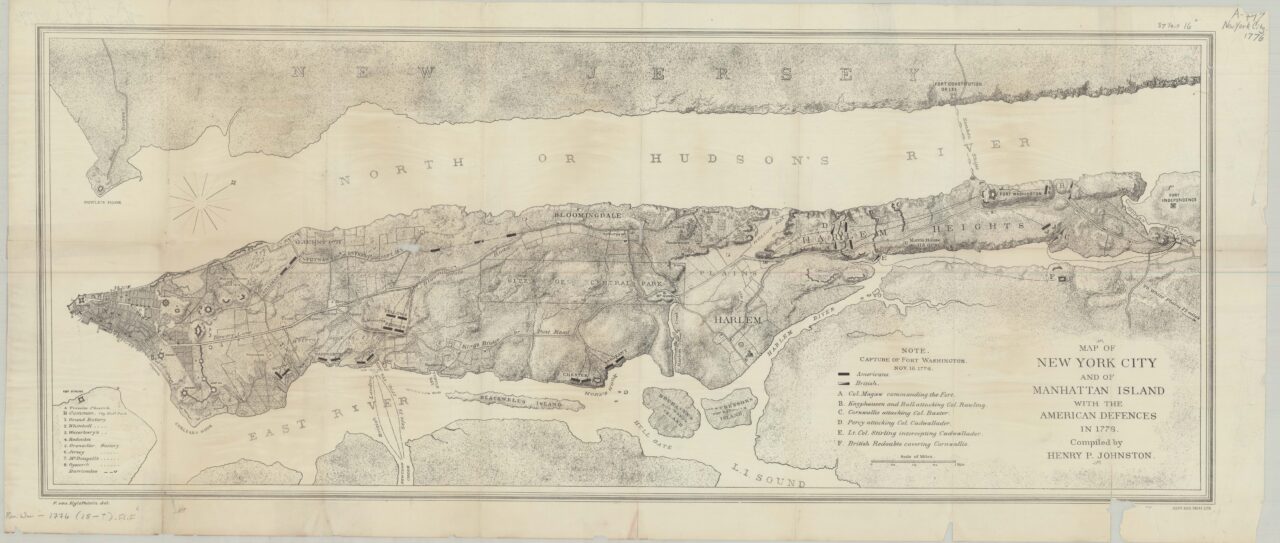

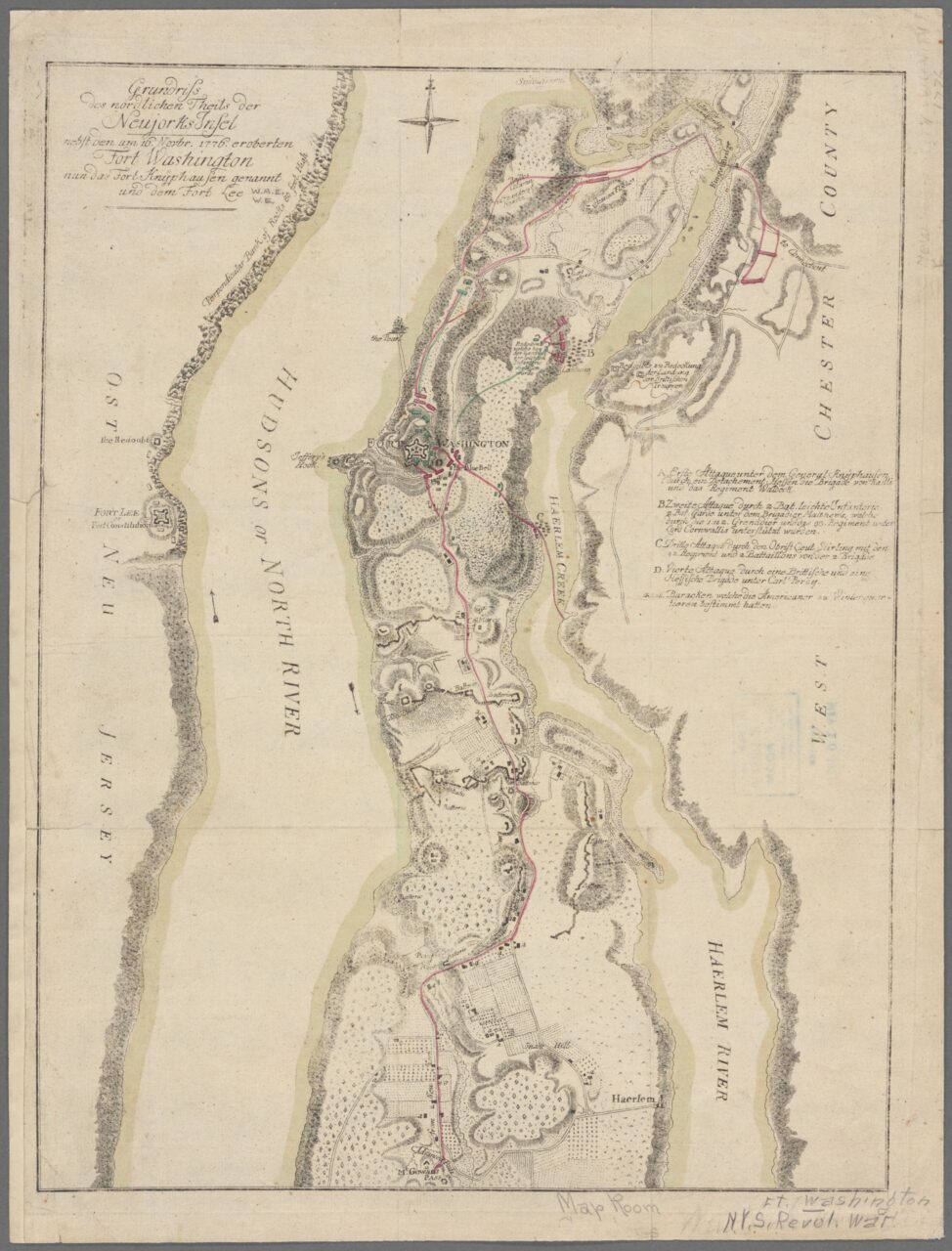

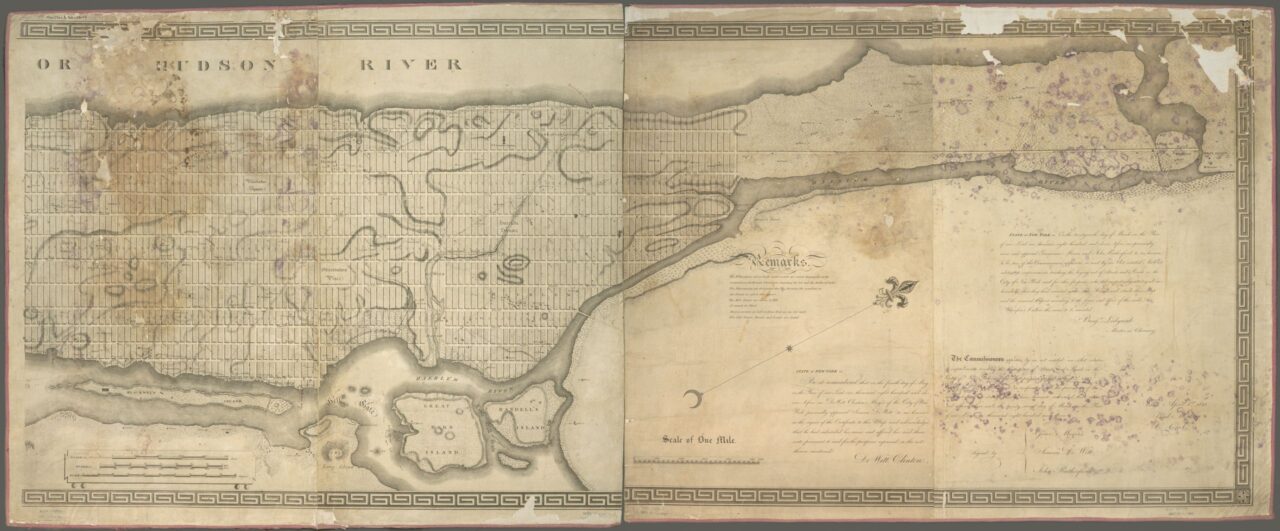

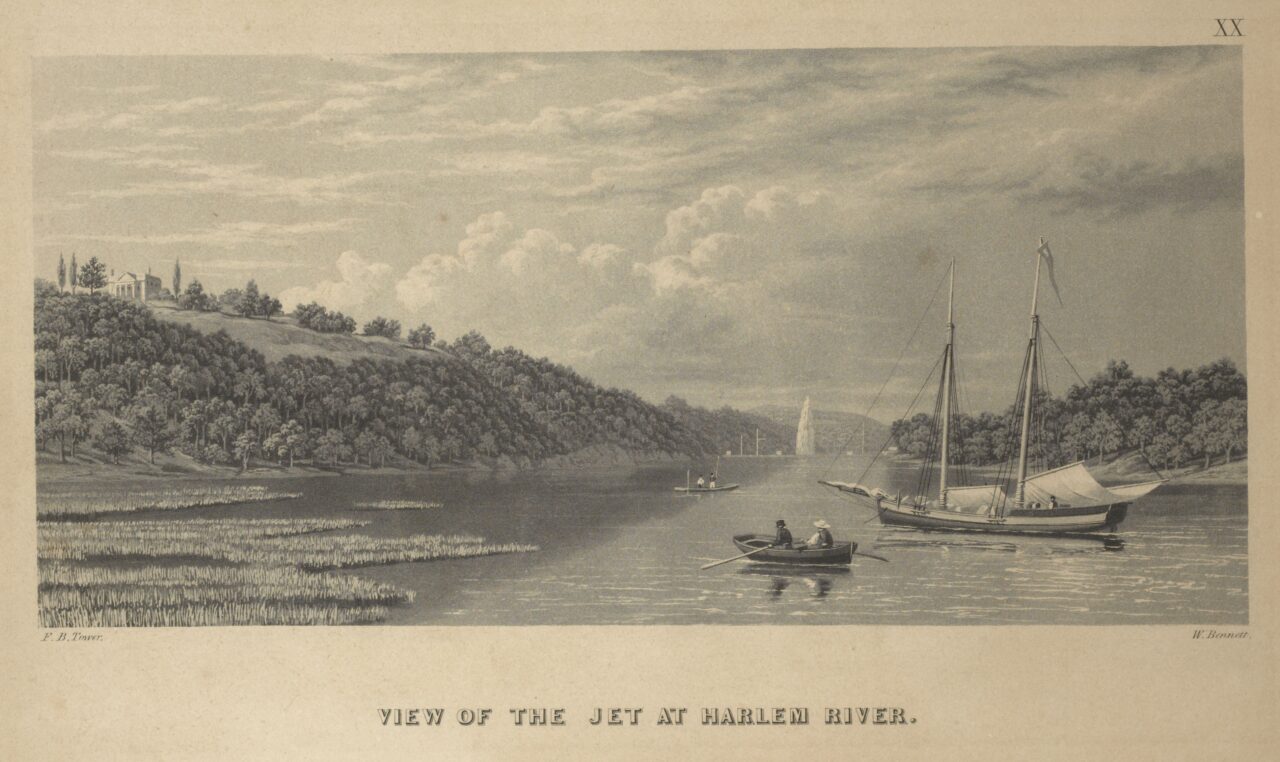

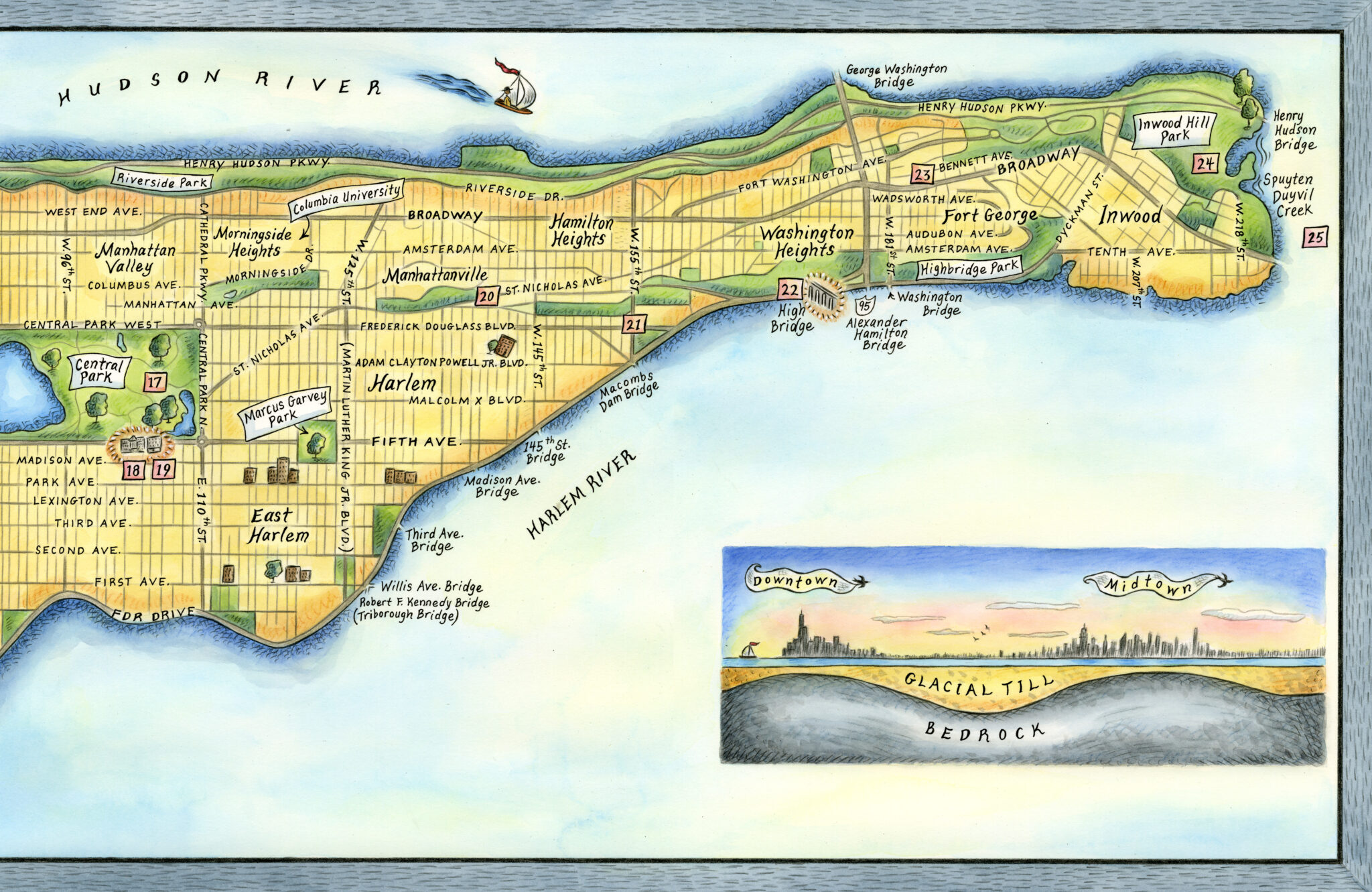

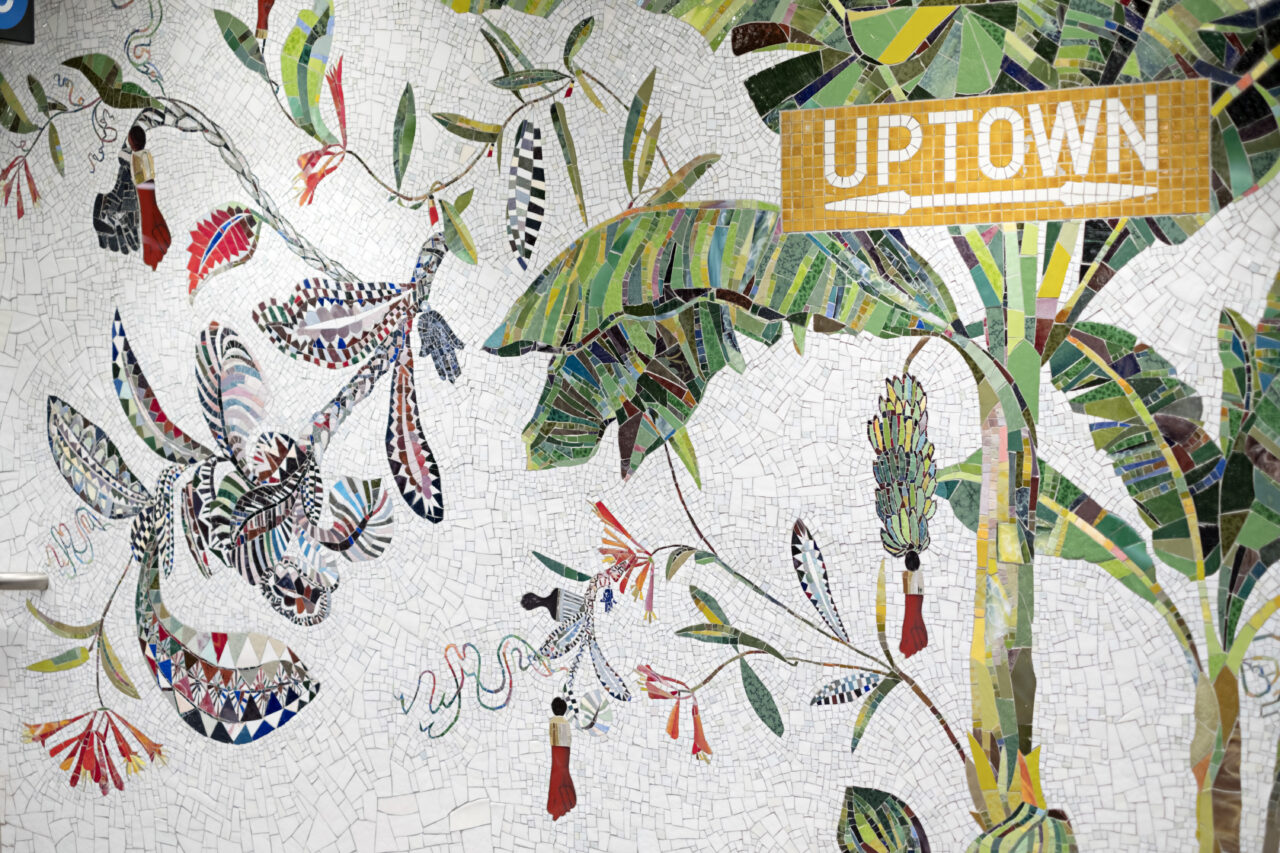

While most of the Dutch settlement of the island was concentrated in the southern portion, Northern Manhattan remained largely untouched by settlers until 1637, when brothers Hendrick and Isaac de Forest and Johannes Mousnier de La Montagne boarded the Rensselaerswijck, a ship from the Netherlands, to claim fertile farmlands north of the New Amsterdam settlement. Three resulting plantations began to take on the character of a permanent settlement, centering around farming, animal husbandry, church, and family. On March 4th, 1658, the Common Council of the City of New Amsterdam passed an eight-point ordinance granting privileges to settlers wanting to come northward to the new settlement named Nieuw Haarlem. It stated that this settlement would be established “for the further promotion of farming[,] for the security of this island and the cattle pasturing thereon [and for] further amusement and development of the city of New Amsterdam.” Within this new village of Haarlem, located from today’s 111th to 125th Streets on the east side of the island, each settler was able to purchase one of the twenty-five village lots of 24-48 acres and six acres of salt meadows, though not adjacent to their village lots. The community, which was a half-day’s march to Lower Manhattan, served as a military buffer for New Amsterdam, and soon included a cattle market and ferry service.

In 1664 when the island became a British colony, Harlem remained a remote outpost with

In 1664 when the island became a British colony, Harlem remained a remote outpost with

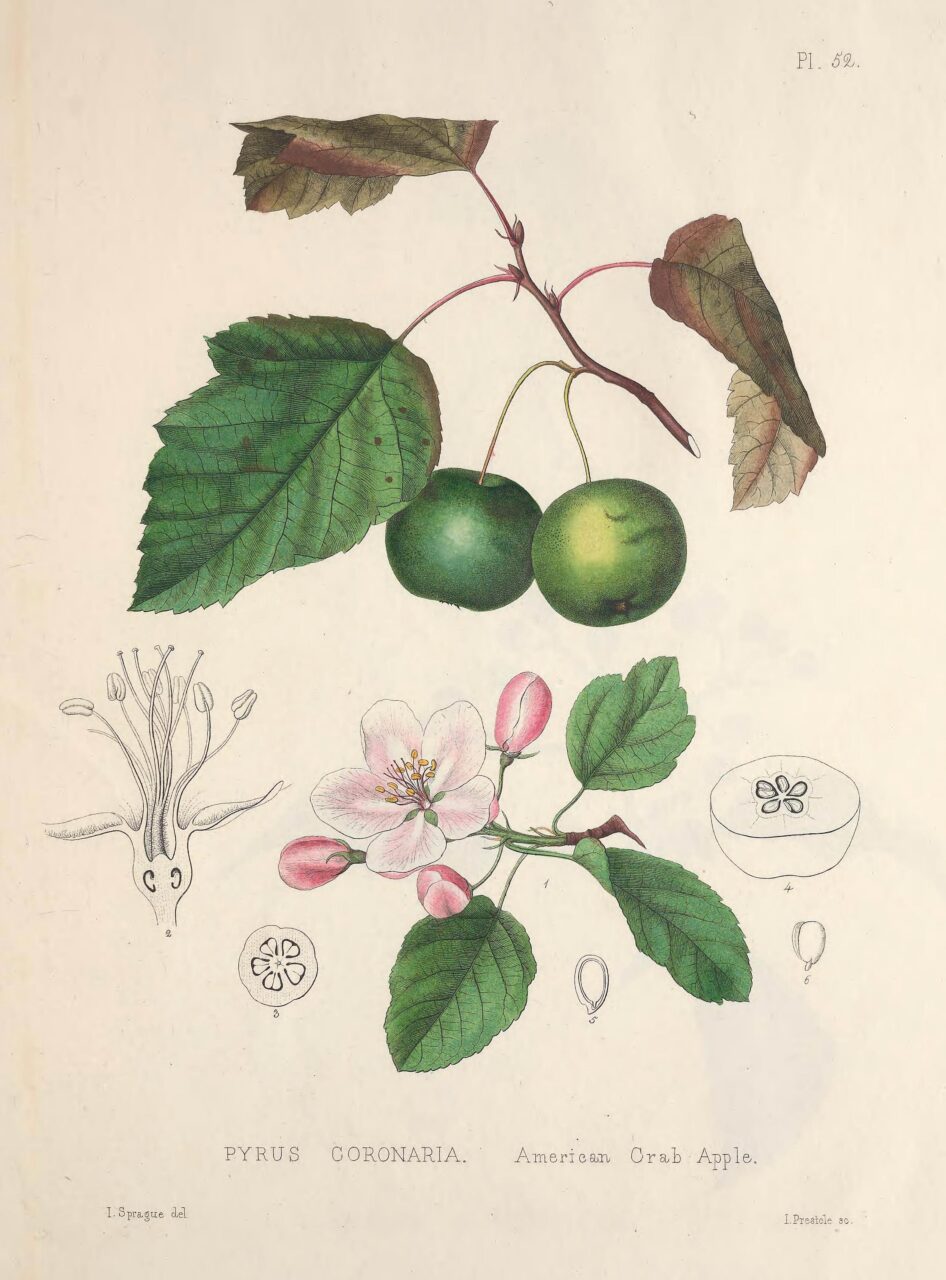

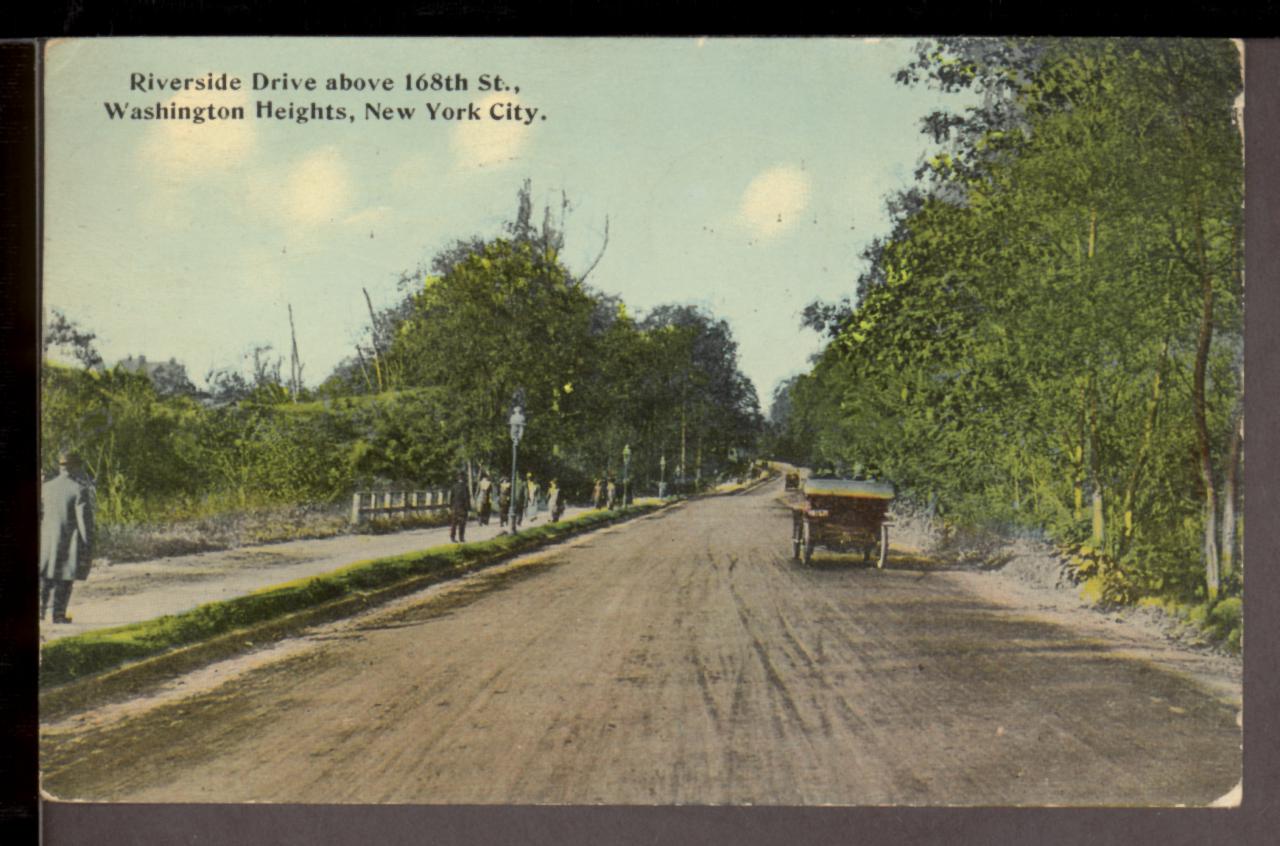

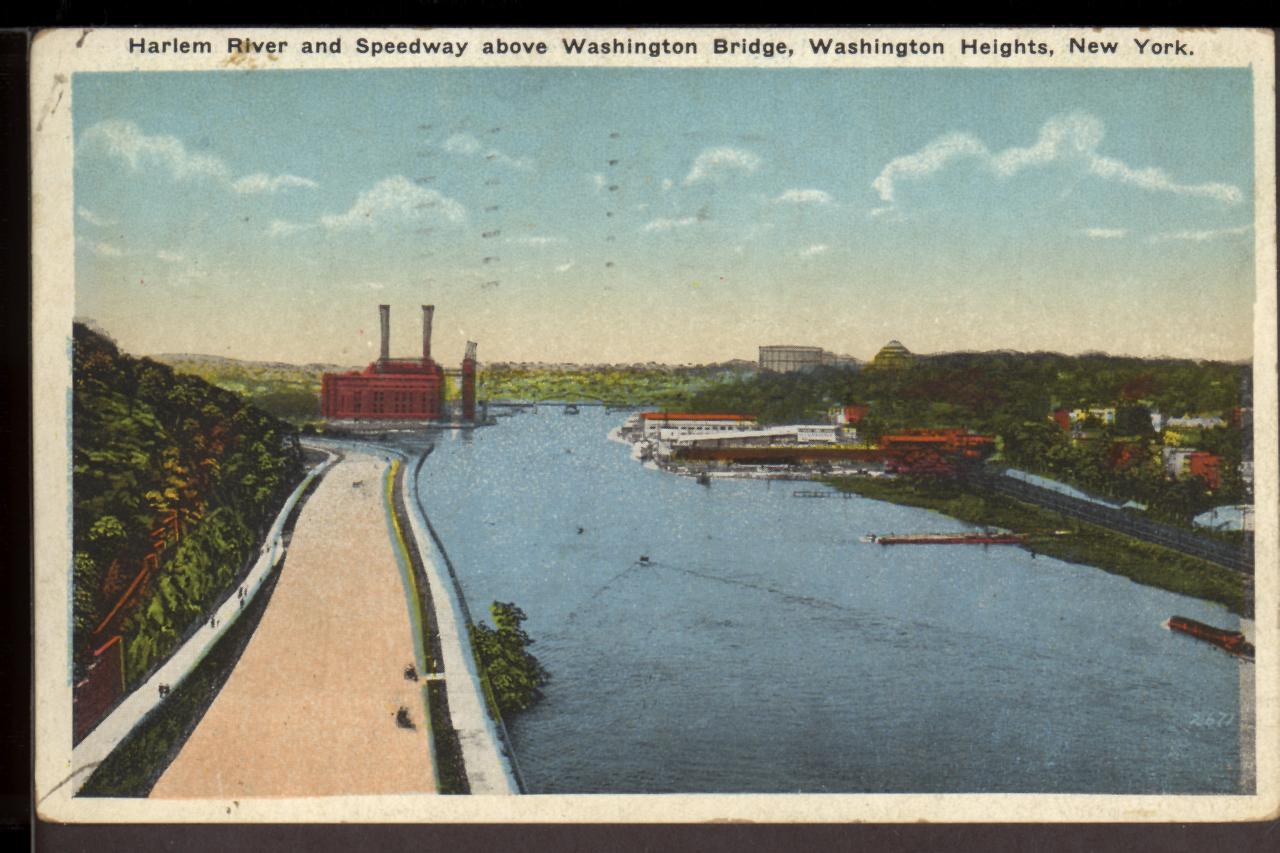

relatively limited businesses and services, while New Amsterdam, now named New York, saw a century of rapid growth and urbanization. In 1666, the first survey of the island was completed and speculators began planning for Harlem’s expansion as a major stop on the Post Road to Boston. Three years later, the governor formed a commission which forced enslaved persons to improve uptown roads, concentrating on leveling and expanding the indigenous footpath that led from the northern tip of the island to New York, which was thought to be “impassable” by settlers. After three years, the road was in such a condition that wagons could travel reliably along the route. However, the road remained remote, in some places traversing across a wilderness inhabited by bears and panthers alongside the Lenape who still remained on the northernmost part of the island. By 1685, the settlers had decimated the wolf population and drove out most of the last remaining Natives. The area around today’s Morris-Jumel Mansion was close to the fork where travelers could choose to take the Post Road down the east side of the island or the Bloomingdale’s Road, later named Broadway, to the west.

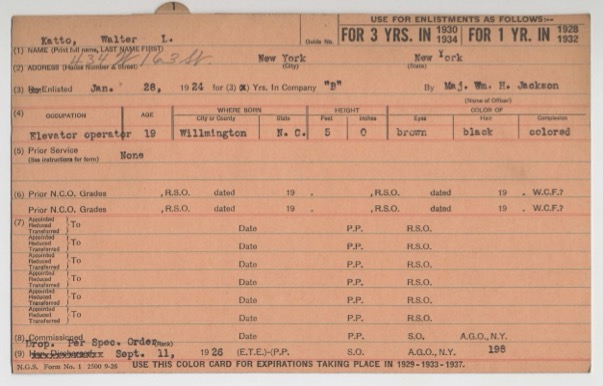

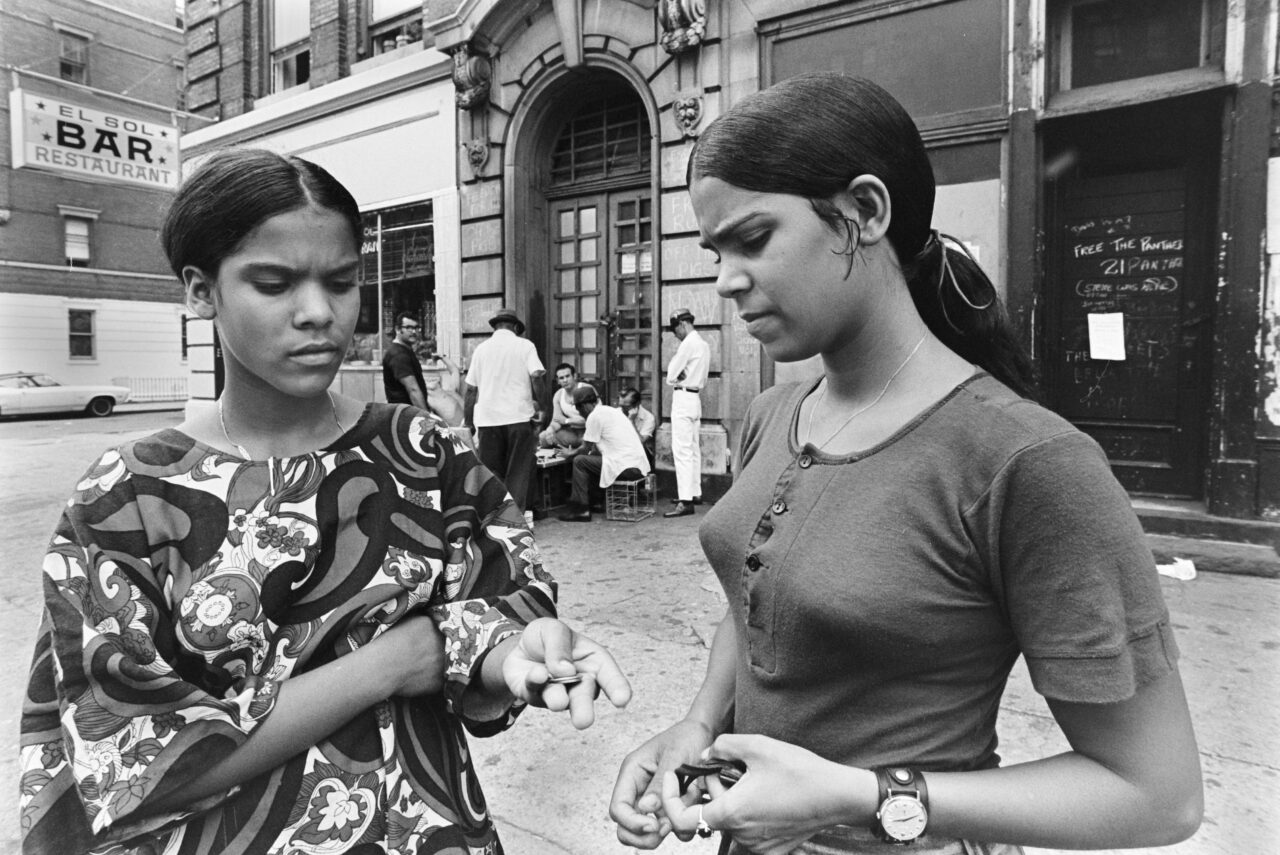

Much economic activity in Northern Manhattan was made possible by the labor of enslaved Africans and indigenous people. In the late seventeenth century, more than a third of the island’s population comprised free and enslaved Africans. Of the few free and enslaved Africans who lived in Haarlem, communities were mostly tiny, self-contained, and relatively independent, with separate markets and establishments for eating, drinking, and entertainment. According to author Jonathan Gill in his book Harlem, Harlem’s Dutch black population “lived in their own homes and continued to work with relative freedom from the discrimination and violence encountered in the southern colonies, which was also becoming more common downtown.”

Race relations remained tense during the British occupation of the island, with new laws and regulations passed to exert more control over people of color. Enslaved individuals now had to carry passes to travel and were prevented from participating in trade with whites, owning guns, or meeting in public in large numbers.

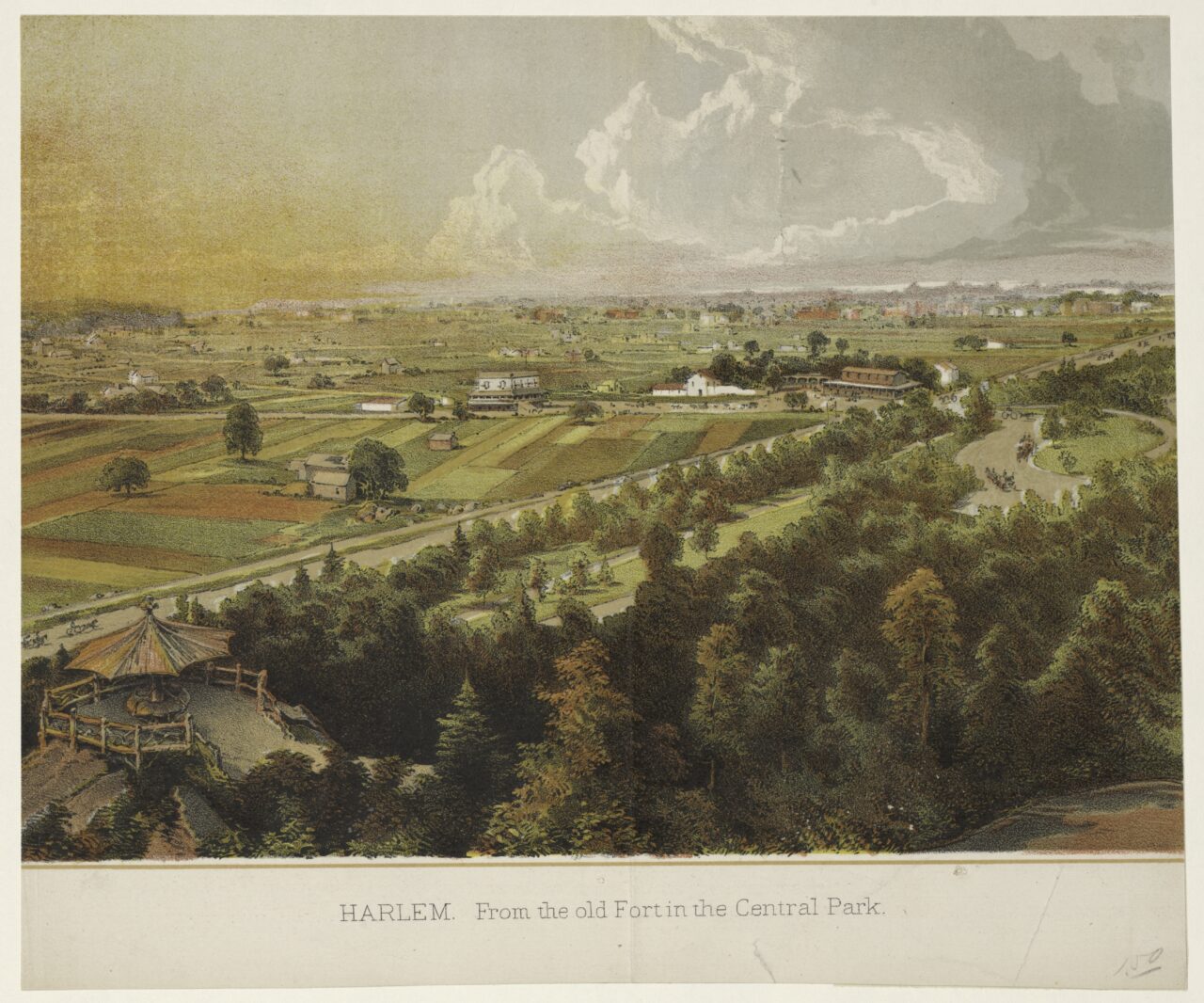

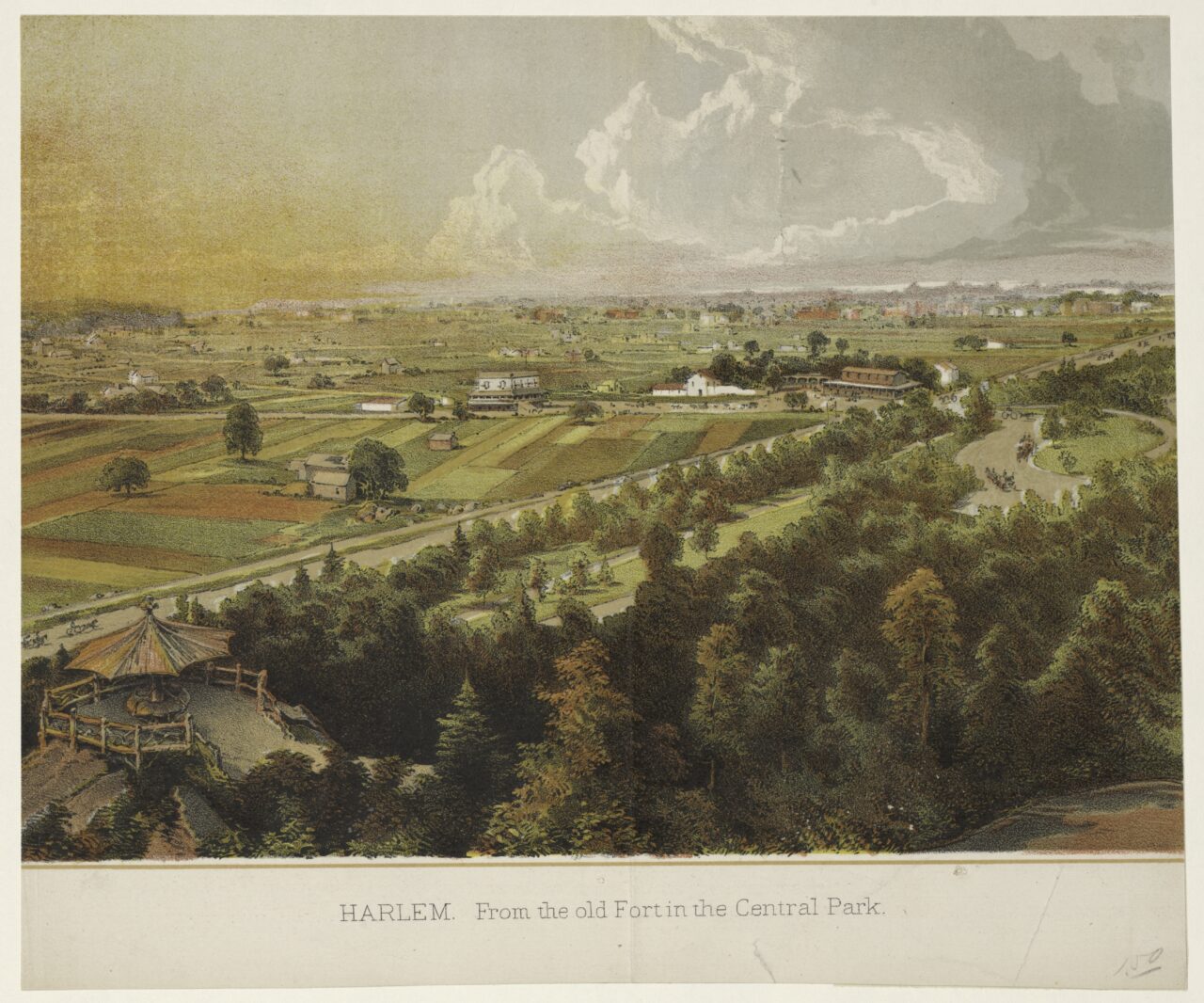

“Harlem,” 1869, The New York Public Library Digital Collections. The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Picture Collection.

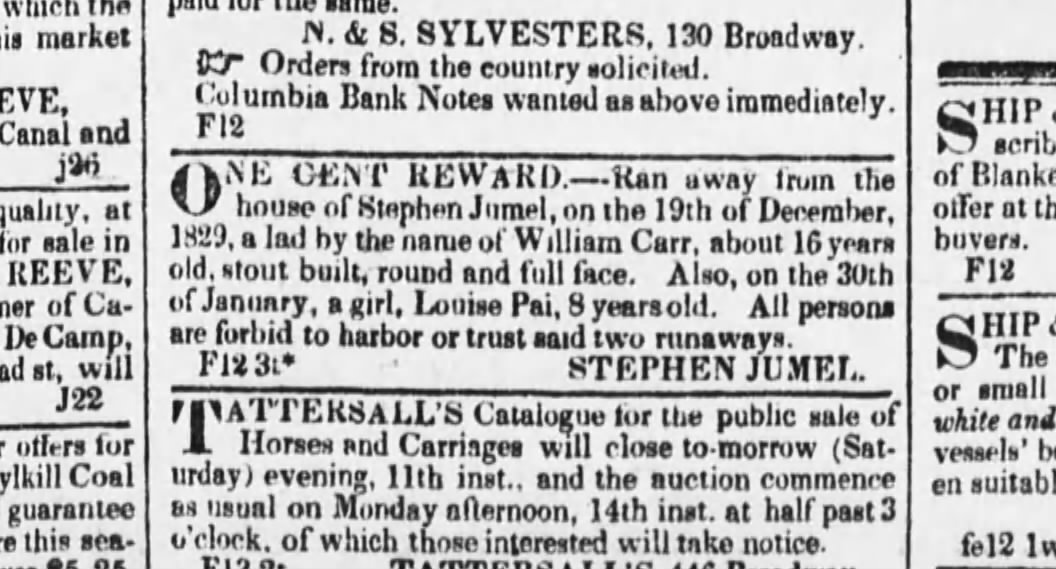

In 1669, one of the enslaved individuals owned by Daniel Tourneu, an early Harlem settler, fled northinto theisland’s dense forests. British officials launched a full-scale police pursuit of the individual, and the escape caused a public outcry. One of Daniel Tourneu’’s sons, Thomas, would later purchase lot numbers sixteen and seventeen from the Township of Harlem – the land that today comprises the Morris-Jumel Mansion.

In 1711, at the time of the creation of the city’s Slave Market, there were eighty-four enslaved individuals in Harlem (then termed the “Out Ward”), which was a quarter of the ward’s population. Over half of Harlem’s white families were enslavers of Blacks.

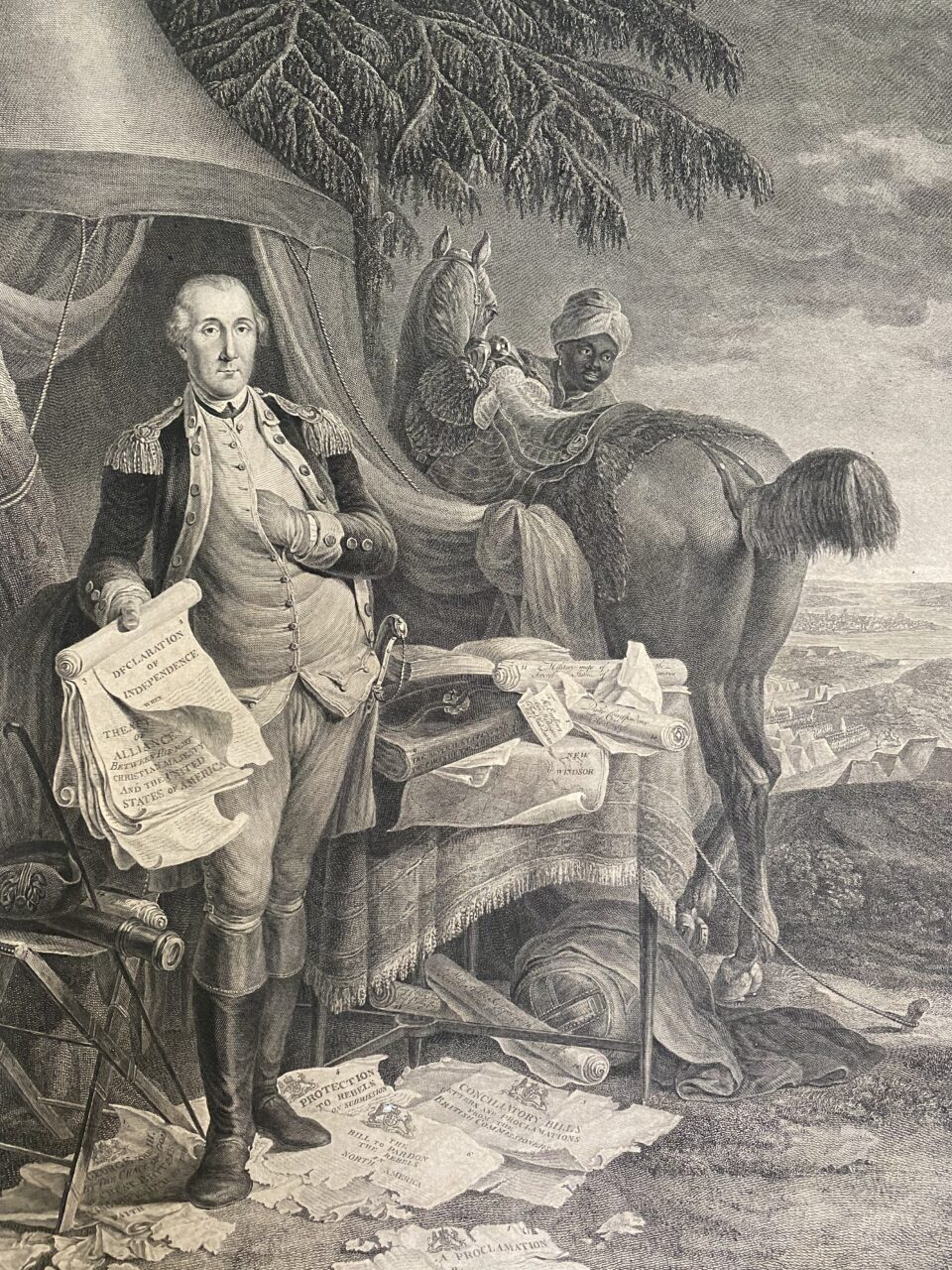

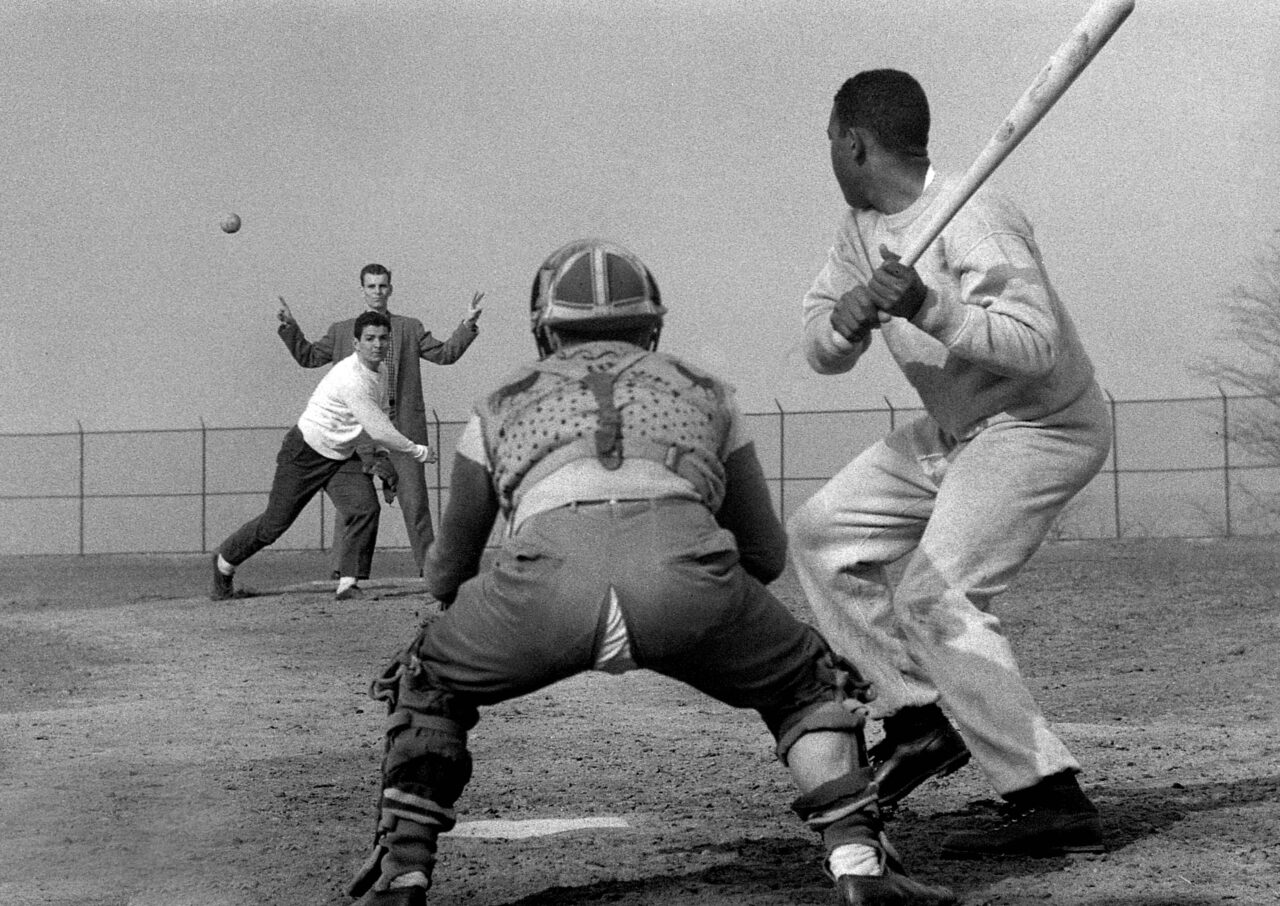

The following year marked the first time that the entire “Out Ward” was properly surveyed. Despite the growing population of the area, most of the land remained thickly forested for subsequent decades. During the mid-eighteenth century, wealthy New Yorkers had country homes built in today’s Northern Manhattan to escape the crime, grime, and disease that was plaguing the rapidly growing city. Soon, the region became known as an entertainment and leisure destination for travelers. However, Harlem’s permanent residents remained deeply influenced by the Dutch way of life and largely favored independence from the British crown.