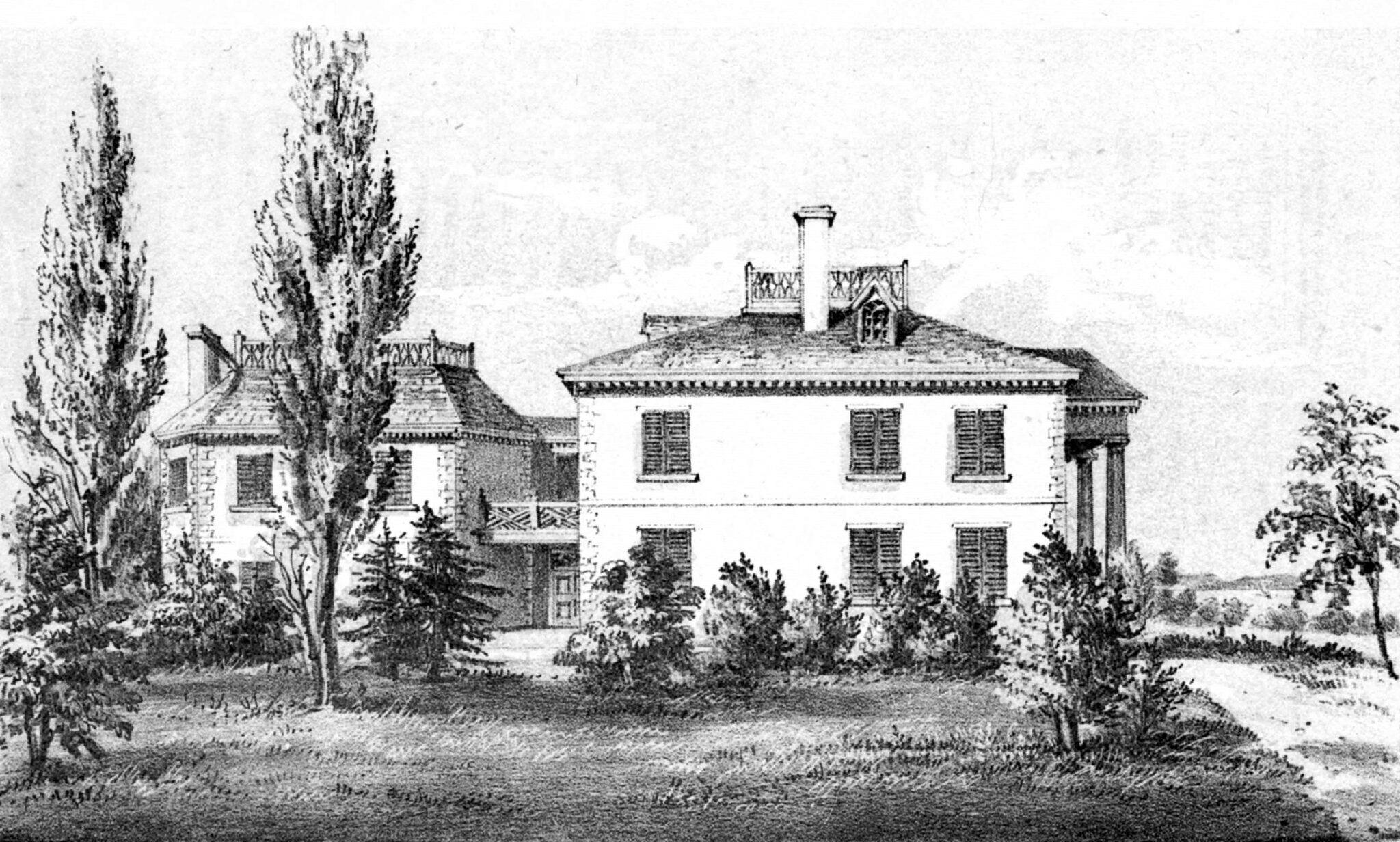

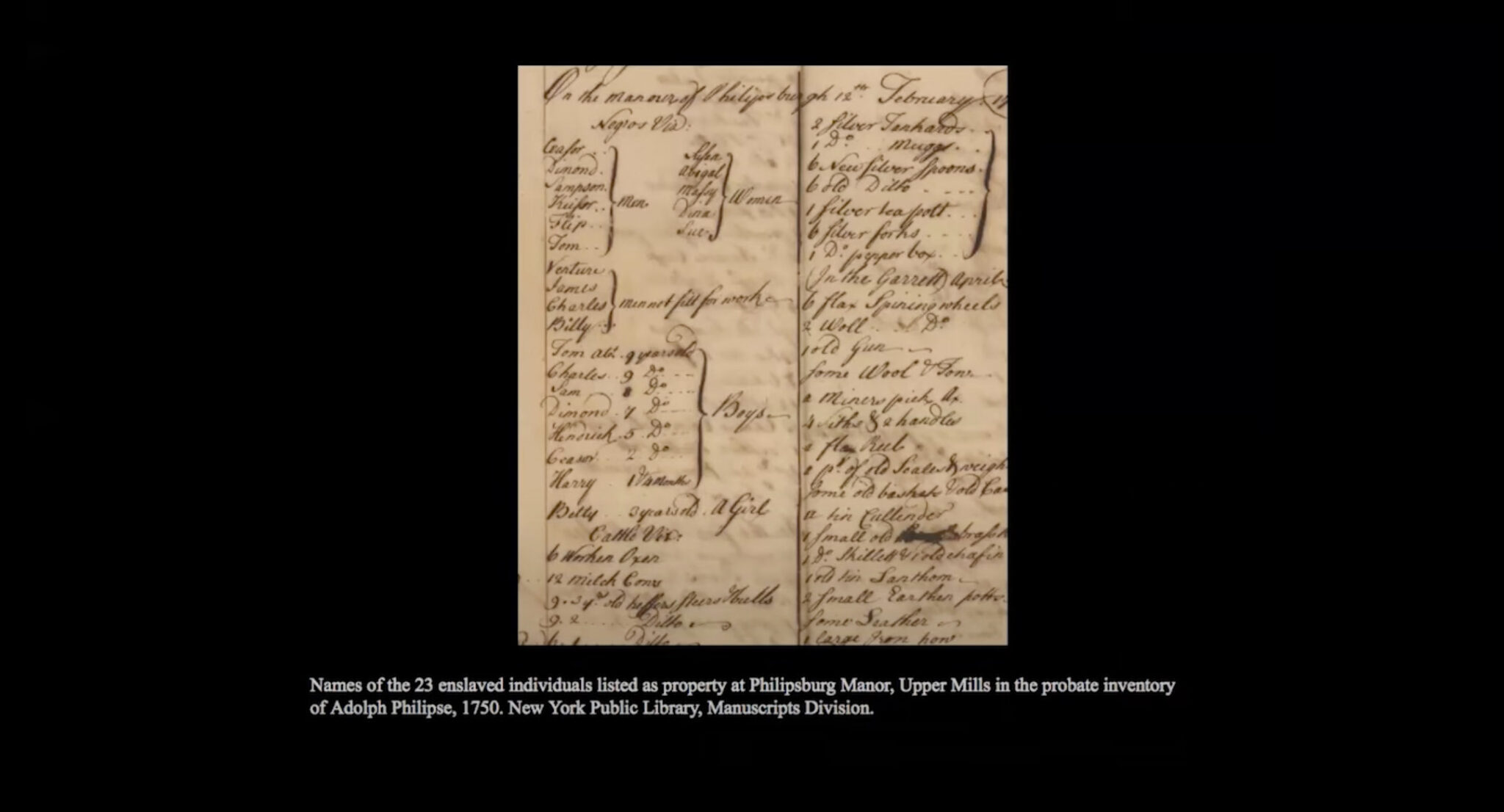

What we now refer to as the Morris-Jumel Mansion was constructed around 1765 as a summer residence for British Colonel Roger Morris (c.1717–1794), his wife, Mary Philipse Morris (1730–1825) and their children. The home, named Mount Morris, was possibly constructed by enslaved laborers whom the Morrises owned or rented from other enslavers. These individuals may have worked alongside free black workers, indentured servants, and other hired labor. The wealth of Anglo-Dutch heiress Mary Philipse afforded the home to be built with progressive architectural details and modern conveniences and allowed for the purchase of over 100 acres of land, from what is likely today’s 159th to 174th Streets. This land, “Lenapehoking,” is the ancestral homeland of the Lenape people.

History of the House

Learn more about the Morris-Jumel Mansion and surrounding land - from the ancestral homelands of the Lenape to the multicultural community of today's Washington Heights

Colonization and the Morris Period (1600s - 1775)

George Hayward, Col. Roger Morris’ House, lithograph, 1854.

Colonel Morris, who was a Loyalist, fought in the French and Indian War (1754-1763) alongside George Washington under General Edward Braddock. After his retirement from the British army in 1764, Morris wanted a summer home that would be a bucolic refuge from the congestion of the downtown city, so he had the house built in the northern part of Manhattan. At the time the city of New York, which ended at today’s Chambers Street, was located eleven miles south of the house.” At the time Upper Manhattan consisted of farmland, forests, and rocky outcroppings and had cleaner water and fresher air than the southern tip of the island. This Georgian-Palladian home, with symmetrical proportions and Classical details, was erected on land acquired once owned by Jacob Dyckman, an early Dutch colonizer.

Inspired by contemporary British residences, the Mansion was possibly inspired by the architectural designs of Morris’s father and uncle, who were both architects. It features very progressive architectural elements for the time and location, including a large dominating portico, a serving alcove in the dining room, and an octagonal-shaped wing which was among the first of its kind constructed in the colonies. Seated atop what was then the second highest point on Manhattan Island, the house provided unprecedented views, including the Harlem and Hudson rivers, present day Westchester County, and as far south as Staten Island.

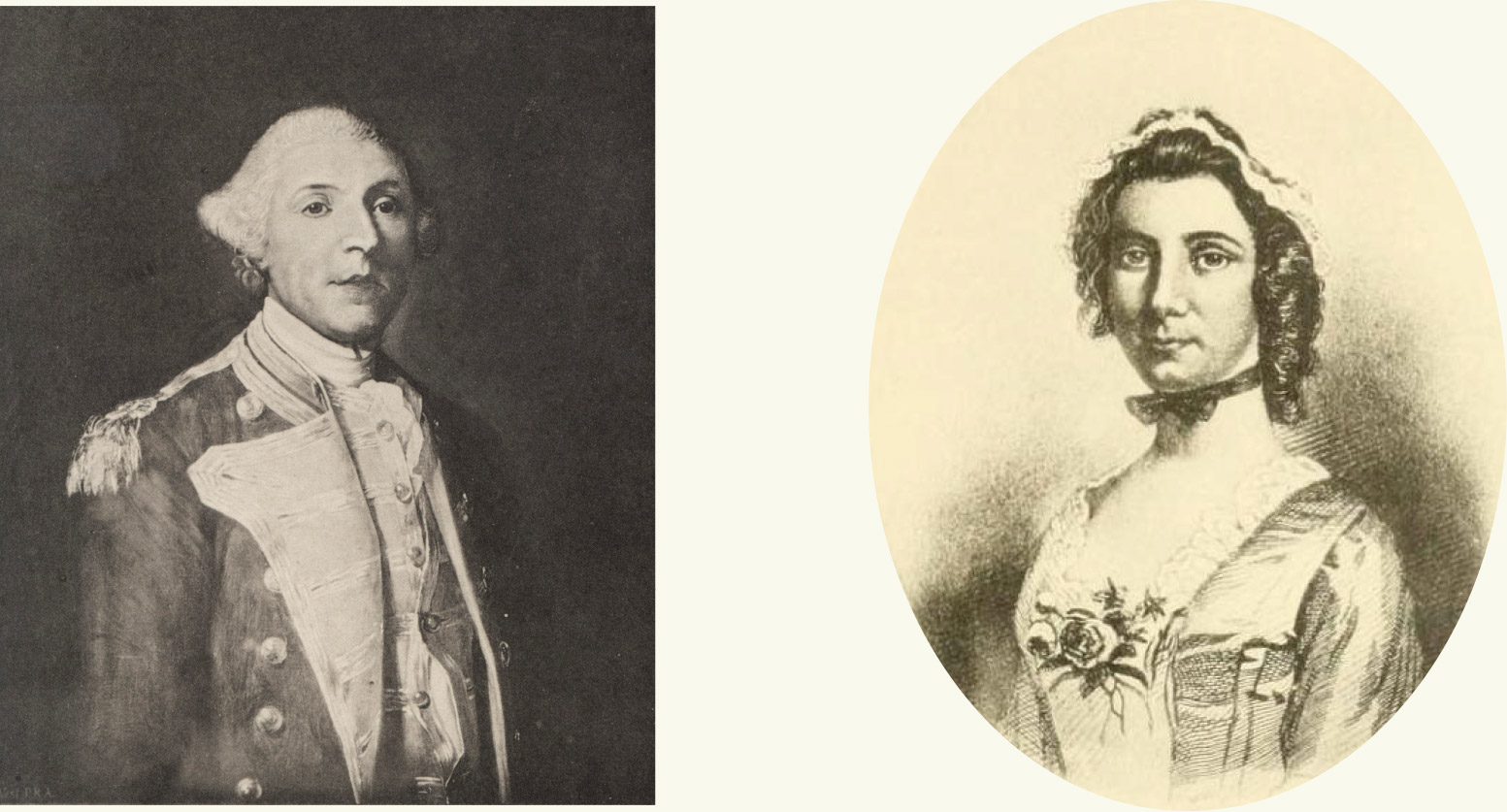

Mary Philipse Morris was a descendant of a prosperous, old Dutch colonial family named the Philipses, whose estates were located further north along the Hudson River. The Philipse family made their fortune in the slave trade and were among the largest enslavers in colonial New York.

Left: Benjamin West, Roger Morris, 1776, Copy print from a painting. Right: Henry Bryan Hall, Miss Mary Philipse, 1880, Engraving

The Morris family lived in town—in what is today downtown Manhattan—on Stone Street, dring much of the year, spending their summer months at Mount Morris. In 1775 British Colonel Morris, a Loyalist, left for London to avoid bringing attention to the Morris family during turbulent, early revolutionary times. His wife, along with four of their five children and servants, most likely including enslaved people, traveled to Philipse Manor Lower Mills in 1776 (now known as Philipse Manor Hall in Yonkers) to escape the escalating conflict of war. Colonel Morris returned to the colonies in December 1777 and presumably stayed in lower Manhattan with his family. He eventually served as Inspector of the Claims of Refugees for the British army in New York from 1779 until 1783.

Revolutionary War & Headquarters of George Washington (1776)

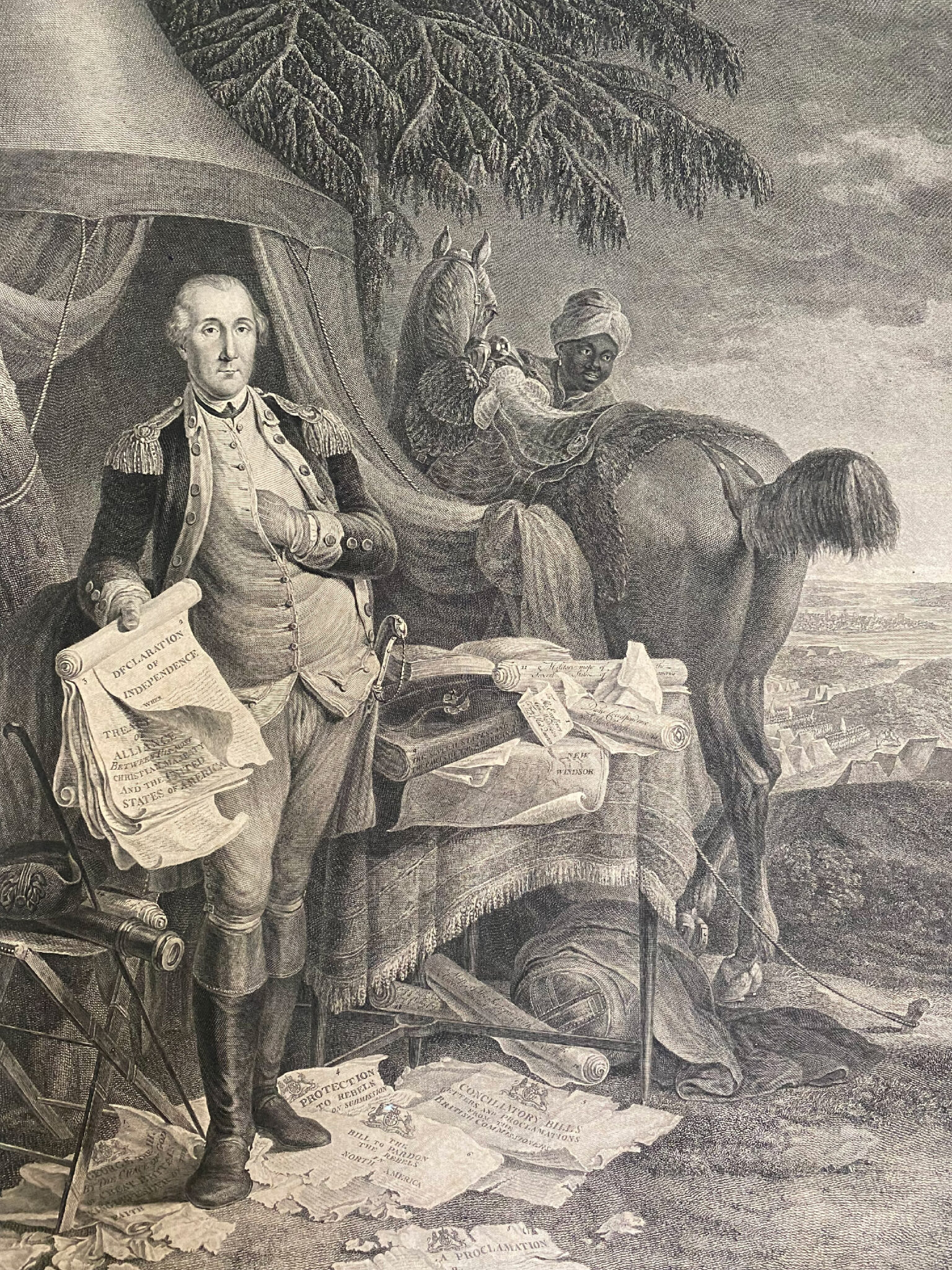

On September 15, 1776, General George Washington occupied the abandoned house with his officers and domestic staff, after the Continental Army’s retreat from Brooklyn, after losing a battle. The elevated location and size of the house made it ideal as a military headquarters during the Revolutionary War. The Battle of Harlem Heights occurred on September 16th, 1776, just south of the house in the area now known as “Manhattan Valley,” near today’s Columbia University campus, and was the first battle where the British retreated from the Continental army. Washington remained in residence for approximately five weeks, and used the second story of the Octagonal Room as his office. It is believed that Washington slept in what is now the William Chase bedroom on the second floor with his enslaved valet, William Lee in close proximity. After Washington departed, the Mansion at various times became the headquarters for other troops until Evacuation Day in 1783, including English General Sir Henry Clinton and later auxiliary German mercenary soldiers, known as Hessians, who were under the command of Baron von Knyphausen. The Mansion is among the few remaining structures in the nation to house all sides of the conflict.

Noël Le Mire, Le Général Washington ne quid detrimenti capiat res publica, 1780, lithograph

Tavern Period & Washington’s Return (1780s-1790s)

After the end of the war, Mary Morris was one of only three women accused of treason in New York, and the property was confiscated as a result of the New York Legislature’s Act of Attainder in 1779 (written by Mary’s cousin, John Jay). The house and land were then sold to help offset the large war debt incurred by the Americans. Between 1783 and 1810, the house was used briefly as a tavern, stagecoach stop and as an inn for travelers before being largely abandoned. The surrounding acreage was used by tenant farmers.

In July 1790, President Washington visited the house with some members of his future cabinet and their wives and families for a formal, lavish meal on the surrounding grounds. Among the guests were Thomas Jefferson, John Adams, Abigail Adams, Alexander Hamilton, Eliza Schyler Hamilton, Martha Washington, Henry Knox, and Lucy Knox. Washington wrote about the visit in his journals and described the house as being “in possession of a common farmer” at that time.

The Jumels, Renovation, and Prosperity (1810-1865)

Twenty years after Washington’s dinner, the house was purchased by the Jumel family. Stephen Jumel, a French wine merchant and well-established importer of luxury goods, married American Eliza Bowen in 1804. Six years later, in 1810, the couple purchased Mount Morris, along with its acreage.

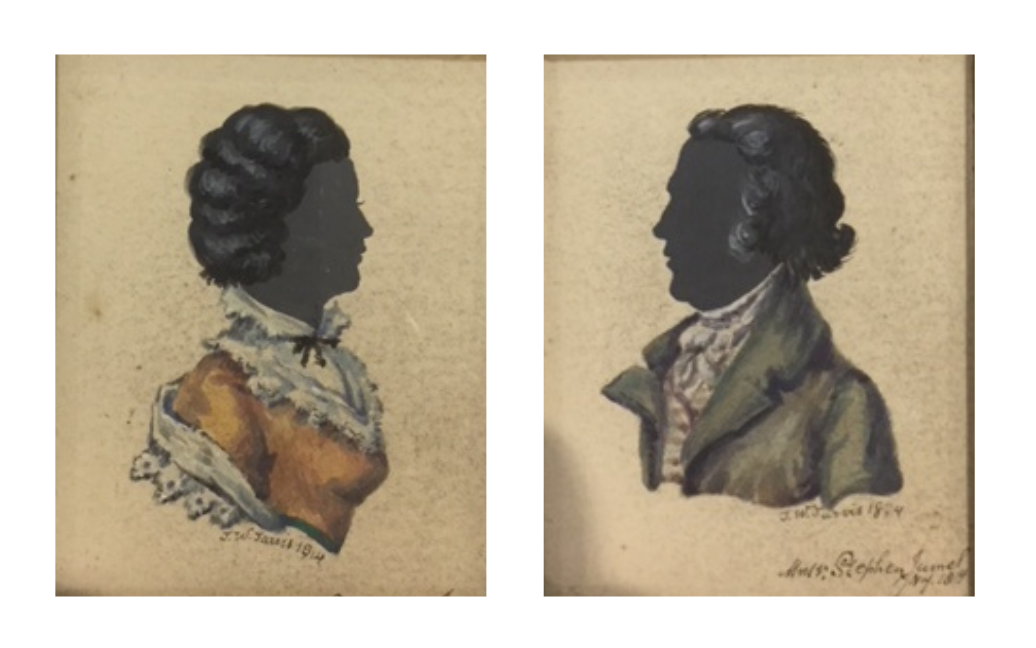

John Wesley Jarvis, Silhouettes of Eliza and Stephen Jumel, 1814.

Eliza grew up in poverty in Rhode Island and was largely self-educated, becoming fluent in French. Later in their marriage she proved to be an astute businesswoman who managed the Jumels’ real estate deals. Despite their wealth, it seemed as though she and Stephen were never fully accepted into the highest echelons of New York society due to their humble and immigrant origins.

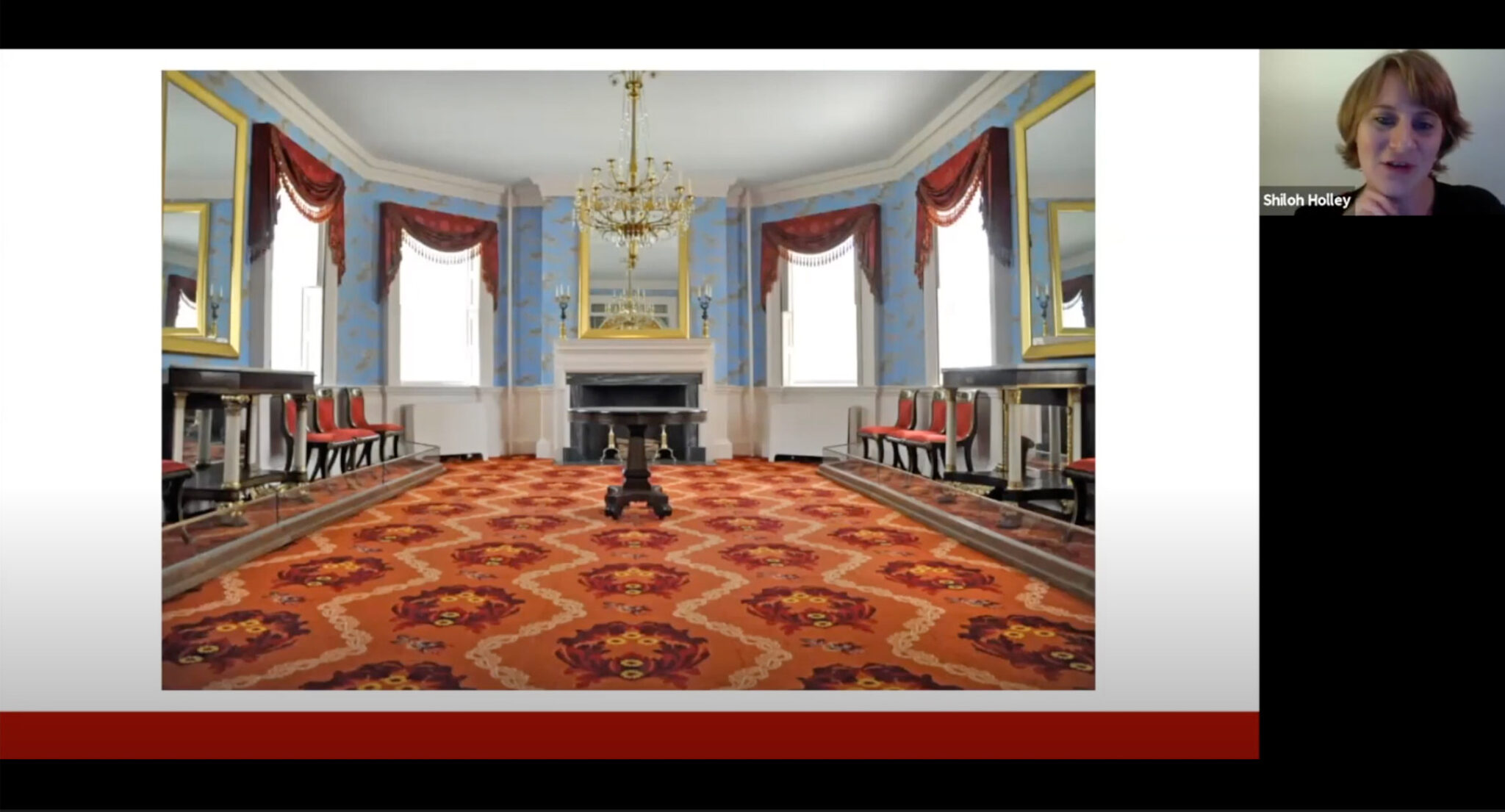

After purchasing the house, the Jumels embarked upon a needed renovation to modernize and repair the residence which had been abandoned for nearly thirty years. Some of the most substantial alterations included the remodeling and expansion of the porch, the extension of the balcony, widening of the entrance portal, and the inclusion of new sidelights and a fashionable fan window containing the stained glass roundels seen today. It is also thought that at this time, access was given to the widow’s walk and the space in the third-floor portico became additional living quarters. Much of the decorative eighteenth-century woodwork in the parlor, library, and two bed chambers was removed. The redecorating campaign of the 1820s included the purchase of a suite of furniture commissioned for the Octagon Room by the Scottish-American Cabinetmaker, Duncan Phyfe (1770–1854).

The Jumels lived in France for a time and records indicate that they were socially connected to the Napoleonic circle. Jumel family tradition suggests that Stephen and Eliza offered to provide Napoleon Bonaparte with safe passage to New York after the Battle of Waterloo. Although Napoleon apparently refused the offer, the Jumels are said to have acquired several of Napoleon’s possessions, including a set of gilt Heraldic wings, a suite of chairs, and a sleigh bed with swan motifs, all of which can be seen exhibited throughout the museum.

Bruce Katz

Stephen died in 1832, and Eliza married her second husband, the former Vice-President Aaron Burr, in the home’s front parlor in 1833. Eliza Jumel filed for divorce four months after the marriage, and hired Alexander Hamilton, Jr. as one of her attorneys handling the divorce. Burr passed away in a Staten Island rooming house the day the divorce was to be finalized in 1836.

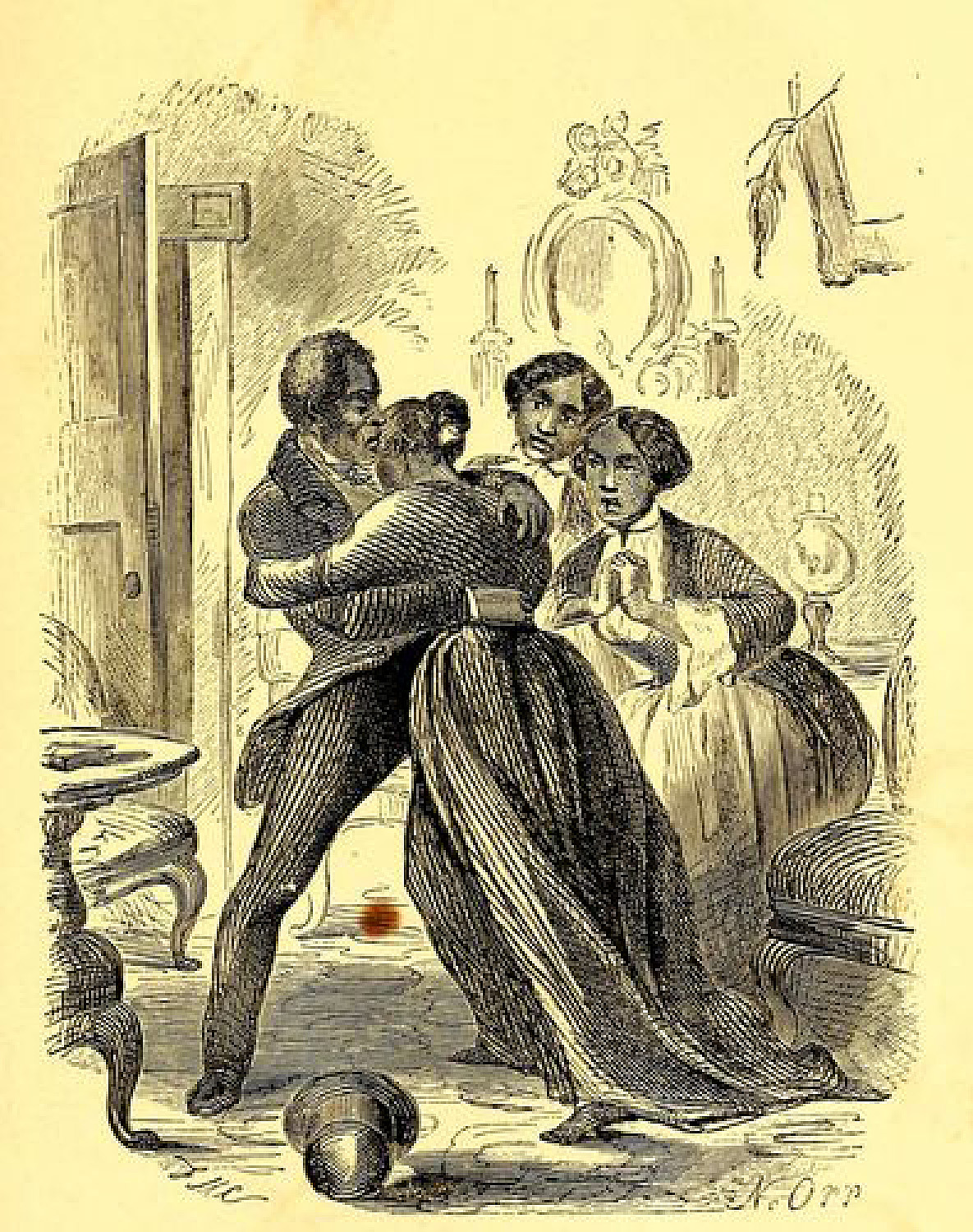

Eliza never remarried but did continue her aspirations to be a part of New York society. She converted the Mansion into her primary residence, and summered in fashionable Saratoga, New York. While in Saratoga in 1841, Eliza hired free African American Anne Northup to be her cook in New York City. Northup’s husband, Solomon, had been abducted and sold into slavery in the South (as recounted in his memoir Twelve Years a Slave). Mrs. Northup and her three children lived with and worked for Eliza and her family at the Mansion or in New Jersey.

Nathanial Orr, “Arrival home, and first meeting with his wife and children.” Originally published in Twelve Years a Slave. Buffalo N.Y.: Miller, Orton & Mulligan, 1853

Later Ownership (1865-1900)

When Eliza died on July 16, 1865, she left the estate to her sister’s children, Eliza Chase (pictured in the largest portrait in the hallway), leaving the other sibling William Chase out of the will. A highly contentious and publicized battle over the estate ensued, and lasted 17 years, ultimately reaching the Supreme Court. The Chases sold the house in 1887.

In 1889, the home became the residence of the early French photographer and filmmaker Augustine Le Prince (1841- aprx. 1890) and his family. Le Prince was a trained chemist and inventor; he rented the mansion with the intention of debuting the first moving motion picture at the residence. However, in 1890, Le Prince and the film disappeared before the film could be publicly shown. His family remained at the house for a short time after while pursuing the circumstances of his disappearance, but Le Prince was never found.

General Ferdinand Earle, his wife Lillie, and their children resided in the home from 1894 until 1903, referring to the estate as Earle Cliff. Following Ferdinand’s death in 1903, Lillie campaigned for the home to be preserved as an historic site, and the City of New York purchased the building and almost two acres for $235,000.

Museum Period (1900-today)

Today, the Mansion and its neighboring buildings are a part of the Jumel Terrace Historic District due to the structures’ historic significance and representations of housing from three centuries. In the 1940s, the neighborhood surrounding the Mansion became home to many luminaries of the Harlem Renaissance. The apartment buildings located at 409 and 555 Edgecombe were among the first complexes in Upper Manhattan to be desegregated. Tenants such as Duke Ellington, Count Basie, Joe Lewis, Andy Kirk, Canada Lee, Kenneth Clark, and Paul Robeson resided in the neighborhood. Artist Elizabeth Catlett, and musicians Lena Horne and Dr. May Edward Chinn (pianist) also lived in these buildings, as did W.E.B. Du Bois, Thurgood Marshall, and Walter White (President of the NAACP). The Mansion, a member of the Historic House Trust of New York City, was listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 1966, followed by its designation as an Individual Landmark in 1967 and Interior Landmark in 1975 by New York City’s Landmark Preservation Commission. During the Bicentennial Celebrations in July 1976, Queen Elizabeth II and Prince Philip of England visited the Mansion and toured the grounds and historic gardens. In 2014, writer and composer Lin Manuel Miranda sat in Aaron Burr’s Bedchamber and wrote songs for his hit musical, Hamilton.

The Mansion today serves as a community space, featuring unique arts, theater, and educational programming to connect the past history of the house and its inhabitants to the present.